I can almost do it; I’m just wrong this year.

Pine Siskins in fall 2015 during the “superflight”. Davis, California.

Boreal seed-eating birds are notoriously unpredictable in their winter wanderings. Unlike a certain distinctive Dark-eyed Junco that once returned to my small apartment patio in Davis, California several winters in a row, these birds of the northern forests have no such allegiance to any patch of land. A Pine Siskin once banded in winter in Quebec turned up in California during a subsequent winter; other Pine Siskins banded in winter in New York and Tennessee spent a later winter in British Columbia; an Evening Grosbeak banded in winter in Maryland spent a later winter in Alberta; a Eurasian Siskin banded in winter in Sweden was later found in Iran; a Common Redpoll once wintered in Belgium, and later in China; another Common Redpoll banded in winter in Michigan was found during a later winter in Siberia (Newton 2006). In other winters, they hardly migrate at all. While up to 90% of band recoveries for many winter-banded species are pretty much where they were banded, that rate fall to about 1% for irruptive boreal species (ibid).

There’s a rich literature focusing on cone crop failure and irruptions of crossbills, redpolls, Clark’s Nutcrackers and other species (Reinikainen 1937, Lack 1954, Svardson 1957, Davis and Williams 1957 and 1964, Ulfstrand 1963, Evans 1966, and Eriksson 1970). To quote Newton (2006), “Clear evidence has emerged that major emigrations follow periodic crop failures.” Most recently, Wilson and Brown (2017) confirmed that Red-breasted Nuthatches are not fleeing bad weather nor are they attracted to specific food elsewhere; they are spreading across the land “because of failure of conifer seed production on the breeding grounds.” They are famine refugees. Other research has shown that, “despite the presumed benefits of irruption as an adaptive response to food shortage when population levels are high, negative population consequences can ensue.” Large irruptions are correlated with smaller numbers on Breeding Bird Surveys the following summer; they don’t all make it back (Dunn 2019).

Another factor, however, is high population densities of the birds (Bock and Lepthien 1976). Koenig and Knops (2001) reached some specific conclusions when they examined 30 years of Christmas Bird Count (CBC) data, focusing on multiple species, and compared it with data on cone crops. They found that Red-breasted Nuthatch, Black-capped Chickadee, Evening Grosbeak, Pine Grosbeak, Red Crossbill, Bohemian Waxwing, and Pine Siskin irruptions were “correlated with a combination of large coniferous seed crops in the previous year followed by a poor crop.” In short, a good year causes a pulse in reproduction, followed by a lean year which causes the expanded population to suddenly roam in search of food. There was some variation, with the good year or the bad year playing a more dominant roll for different species, but for most species, it was both. (And for Purple Finch, it seemed to be neither.) They concluded that “seed crops of boreal trees play a pivotal role in causing eruptions for a majority of boreal species, usually through a combination of large seed crop resulting in high population densities followed by a poor seed-crop, rather than seed-crop failure alone.”

Red-breasted Nuthatch, also in Davis in fall 2015.

A year previously, Koenig and Knops (2000) studied just the trees, and concluded that various tree species often boom and bust in sync. They noted that “the large geographic scale on which seed production patterns are often synchronized, both within and between genera, has important implications for wildlife populations dependent on the seeds of forest trees for food. In general, resident populations of birds and mammals dependent on mast are likely to be affected synchronously over large geographic areas by both bumper crops providing abundant food and, perhaps even more dramatically, by crop failures.” Newton (2006) reported synchrony in boreal conifer seed production in forests 1000 km apart. Strong et al (2015) links Pine Siskin irruptions to continent-wide winter climatic patterns.

With synchronized cone crop failures, one would expect synchronized irruptions across bird species. The literature on this is supportive but mixed. Bock and Lepthien (1976) provide nice annual maps by species illustrating “generally synchronous” irruptions in many (but not all) years. Koenig (2001) offers the most comprehensive analysis, exploring synchronous irruptions among all combinations of 15 species, including multi-year lagged effects. (Here it’s important to understand correlation coefficients, or Pearson’s r. For guidance in interpreting r, 1.00 would be a perfect match, 0 would mean no correlation, and -1.00 would mean they do the exact opposite of each other.) Koenig’s highest correlation coefficients between two species were generally between 0.30 and 0.50. He also shreds an earlier assertion from Bock (1999) that there is strong correlation between Common Redpoll and Pinyon Jay irruptions; there was, but it didn’t last long.

Here I examine 49 years of CBC data (1970-2018) for Red-breasted Nuthatch, Pine Siskin, and Red Crossbill from the northern Central Valley of California, centered around Sacramento. I used data from eight CBCs: Caswell-Westley, Folsom, Lincoln, Marysville, Rio Cosumnes, Sacramento, Stockton, and Wallace-Bellota. I didn’t have any data on cone crops, but I assumed they might be correlated with precipitation the previous year, so I looked at snowfall. In short, I find some support for Koenig and Knops, but I wouldn’t bet more than a beer on it in any given year.

Here are the results. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

First, there are no units for the vertical axis. That’s because the units I used for the birds is basically an index. I converted them all to natural log (ln) because the numbers of siskins, which often occur in large flocks, dwarfed the nuthatches and crossbills. Converting to natural logs put them all more on a level playing field. What you’re seeing is the natural log of total individuals across all eight CBCs each year. (In most years, most birds were in the Sacramento CBC.) The blue circles are the water content (in inches) of the deepest observed snowpack from winter snow surveys at Upper Carson Pass from the previous winter. For example, the large irruption (or “superflight”) in 2015 occurred in the fall and winter of 2015-16, and the very low blue circle on that column is associated with the snowpack from the winter of 2014-15. In general, the snow surveys occurred in Jan-Apr and the CBCs in December of the same year.

A few quick observations from the chart:

- Red Crossbills only occurred in six of the 49 winters, but 4 of those were during nuthatch/siskin irruptions. The only large crossbill irruption occurred in 2015, on top of the largest combined nuthatch/siskin invasion. The 2015 superflight also coincided with the lowest snowpack the previous winter, which came at the end of a four-year drought. So 2015, as an extreme event, tells us a few things. Previous snowpack is important, and correlation across species does occur.

- Most of the other highest irruption years (1981, 1987, 1992, 2012) all came after low snowpack years, and all had higher snowpack the year before that, exactly what Koenig and Knops would predict.

And now for some math:

- The correlation coefficient between nuthatches and siskins is 0.32, so they do tend to irrupt together-ish, but not always and certainly not in the same magnitude. Koenig writes, “For Red-breasted Nuthatch and Pine Siskin, synchrony over different 10-year periods varied from a high of 0.82 (1965-1974) to a low of 0.24 (1987-1996).” His sample included eastern North America, which he showed follows different patterns than the West.

- I then looked at correlation between the cumulative nuthatch/siskin/crossbill irruptions (in natural log, so the full blue, yellow, and red columns in the graph) and a variety of other parameters. Here are the results:

- Correlation with previous winter’s water content from snowpack (the blue circle): -0.44.

- Correlation with water content more than 5″ below average: 0.41.

- Correlation with multiple years of drought: 0.37.

- Correlation with a 10″ drop in water content from the year before that (thus going from a good year to a worse year): 0.38.

- Correlation with the same 10″ drop in water content, but only if the recent year was below average (thus, going from a good year to a bad year): 0.40.

So these correlations all lean in the right direction, supporting Koenig and Knops’ notion that bad years are bad, and bad years after good years are even worse. I would also add that bad years after bad years (a drought) are also bad.

These correlations come with some caveats. First, the correlation between snow water content and cone crop is imperfect. Koenig and Knops (1999) state that, while recent precipitation is indeed an important variable, it’s not the only one. Spring and summer temperatures play a role in cone development, as well as previous seasons. After a really good year, trees need a break, regardless of rainfall, and will produce less. An example might be 1984, where there was an irruption after an average snow year, but two really heavy precipitation years preceded that.

Another source of noise in the data is that our birds, especially the siskins, may be coming from much further afield than Tahoe. (I deliberately left out Evening Grosbeak because call types from our last invasion suggested the birds were brooksi from Washington state or somewhere up there.)

Donner Pass without snow. January 20, 2015.

While it may seem that the data on irruptions and snowpack tell a compelling story, let’s not forget the present. It’s fall 2019 and we’re in the midst of a significant Red-breasted Nuthatch irruption (and I’ve seen one siskin as well). This year is not on the graph above, but we do already have the snowpack data from earlier in the year. It was way above average. Thus, we’ve just gone from an average snowpack year in 2018 to above-average in 2019, the opposite of what should prompt an irruption. If you bet me a beer, I’d owe you one.

References

Bock, C.E. 1999. Synchronous Fluctuations in Christmas Bird Counts of Common Redpolls and Piñon Jays. The Auk 99: 382-383.

Bock, C.E. and L.W. Lepthien. 1976. Synchronous eruptions of boreal seed-eating birds. American Naturalist 110: 559- 571.

Davis, J. and L. Williams. 1957. Irruptions of the Clark nutcracker in California. Condor 59: 297–307.

Davis, J. and L. Williams. 1964. The 1961 irruption of the Clark’s nutcracker in California. Wilson Bulletin 76: 10–18.

Dunn, E.H. 2019. Dynamics and population consequences of irruption in the Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis). The Auk 136.

Eriksson, K. 1970. Ecology of the irruption and wintering of Fennoscandian redpolls (Carduelis flammea coll.). Annals Zoologica Fennici 7: 273–282.

Evans, P.R. 1966. Autumn movements, moult and measurement of the lesser redpoll, Carduelis flammea. Ibis 106: 183–216.

Koenig, W.D. 2001. Synchrony and Periodicity of Eruptions by Boreal Birds. The Condor 103: 725-735

Koenig, W.D. and J.M.H. Knops. 2000. Patterns of annual seed production by Northern hemisphere trees: a global perspective. American Naturalist 155: 59-69.

Koenig, W.D. and J.M.H. Knops. 2001. Seed-crop size and eruptions of North American boreal seed-eating birds. Journal of Animal Ecology 70: 609-620.

Lack, D. 1954. The Natural Regulation of Animal Numbers. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Larson, D.L. and C.E. Bock. 1986. Eruptions of some North American seed-eating birds. Ibis 128: 137-140.

Newton, I. 2006. Advances in the study of irruptive migration. Ardea -Wageningen 94: 433-460.

Reinikainen, A. 1937. The irregular migrations of the crossbill, Loxia c. curvirostra, and their relation to the cone-crop of the conifers. Ornis Fennica 14: 55-64.

Svardson, G. 1957. The ‘invasion’ type of bird migration. British Birds 50: 314-343.

Ulfstrand, S. 1963. Ecological aspects of irruptive bird migration in Northwestern Europe. Proceedings of the International Ornithological Congress 13: 780–794.

Wilson Jr., W.H. and B. Brown. 2017. Winter Movements of Sitta canadensis L. (Red-breasted Nuthatch) in New England and Beyond: A Multiple-scale Analysis. Northeastern Naturalist 24.

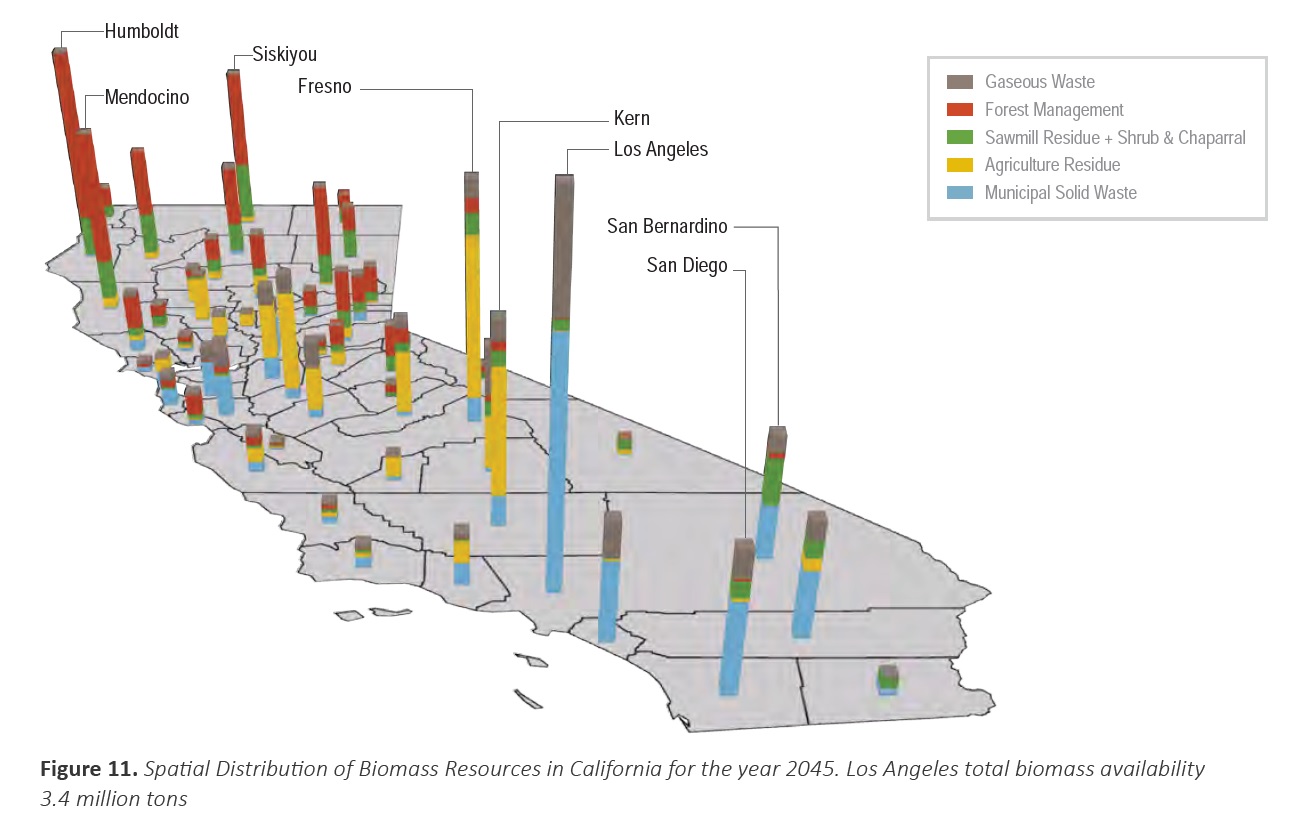

In January 2020, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory released their detailed report

In January 2020, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory released their detailed report

Chapter 7 dives into the logistical details and infrastructure needed to connect the gathered biomass to the biomass fuel plants and the DAC plants to underground storage reservoirs. Among their main conclusions:

Chapter 7 dives into the logistical details and infrastructure needed to connect the gathered biomass to the biomass fuel plants and the DAC plants to underground storage reservoirs. Among their main conclusions:

Many think of Pink-footed Shearwaters as a relatively common bird on West Coast pelagic trips. I like to call them the “photographer’s shearwater” because they invariably offer great photo ops off the back corner of the boat. But they are considered endangered by Chile, threatened by Canada, and vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). They could easily be called the Chilean or even Isla Mocha Shearwater, as the entire world’s population comes from just three islands off the coast of Chile, 85% from Isla Mocha, and the remaining 15% from Santa Clara and Robinson Crusoe Islands in the Juan Fernandez group.

Many think of Pink-footed Shearwaters as a relatively common bird on West Coast pelagic trips. I like to call them the “photographer’s shearwater” because they invariably offer great photo ops off the back corner of the boat. But they are considered endangered by Chile, threatened by Canada, and vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). They could easily be called the Chilean or even Isla Mocha Shearwater, as the entire world’s population comes from just three islands off the coast of Chile, 85% from Isla Mocha, and the remaining 15% from Santa Clara and Robinson Crusoe Islands in the Juan Fernandez group.