Whether you want to nerd out on gull molt or argue over Olympic vs Glaucous-winged Gull criteria, this is your one-stop shop. This is my primer on gull identification and frequency in Puget Sound, from the perspective of Port Townsend. Most of these pics are from Port Townsend or elsewhere on the Olympic Peninsula, though a few are from farther afield.

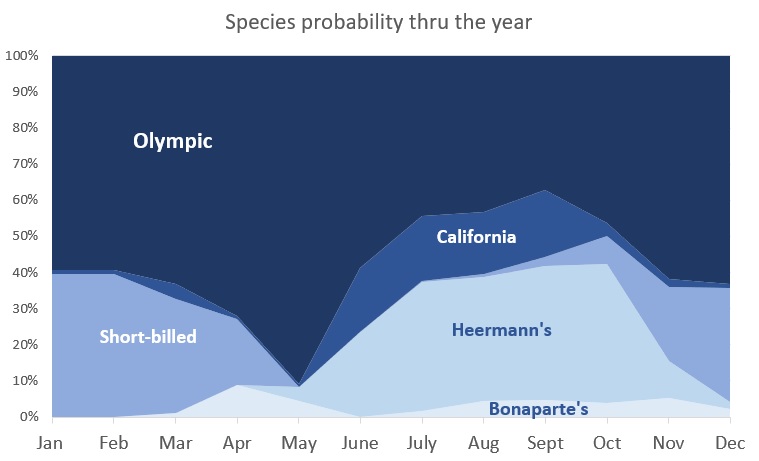

I present them roughly in order of abundance. I start with the forms I see in numbers at various times through the year: Olympic, California, Short-billed, Heermann’s, and Bonaparte’s.

Then I move onto others I see in small numbers: Glaucous-winged, Ring-billed, Thayer’s Iceland, and Herring.

These regularly-occurring forms can practically be identified by bill, head, and body shape. These are all first cycle birds here. A word of caution: there is some variability in bill shape – and it can really change from one still photo to another based on angle and lighting. Also, male gulls are 15-20% larger than females, so size can be a moving target.

Finally, I cover some I rarely see: Western, Cook Inlet, and Glaucous.

Gulls take several years to reach adulthood – three for the smaller gulls, four for the larger ones. During this time, they molt and fade and molt and fade. Season is everything. Gull identification in fall, when the birds are fresh and crisp, is completely different from spring and summer, when they are a faded, tattered mess. With each of these taxa, I’ll present the photos in order of age, so we’ll follow them as they age thru the months and thru the years.

Western x Glaucous-winged Gull (“Olympic Gull”)

Let’s start with the most common gull year-round – by far (with a few exceptions as noted below). When I’m birding, my default position is that all large gulls are Olympics until proven otherwise. (Personal shoutout to Shonn Morris for educating me about Olympic vs Glaucous-winged identification.) The nickname Olympic Gull was possibly first coined by Bob Boekelheide on a Tweeters post on January 13, 1997. Puget Sound Gull was another term batted about at the time.

Hybridization between these two species has been documented since 1908. A nice summary of the early observations, entirely on the outer coast from British Columbia to Oregon, can be found in Scott (1971). Bell’s thesis in 1992 described “a broad zone of introgression” from Haida Gwaii to Coos Bay. The colony at Protection Island, just around the corner from Port Townsend, has been described as the largest Olympic Gull colony in the world (Megna et al 2014). As described in that paper (see Figure 2 at right), the gulls in Puget Sound are decidedly toward the Glaucous-winged end of the spectrum, and “few individuals” appear to be pure Glaucous-winged. Note this is base on appearance, not DNA testing. This implies a hybrid swarm that has been going on for many generations. We are way past F1 hybrids. We’re more at F50 or more. In this context, Megna et al found evidence of assortative mating, meaning that paler birds were more likely to mate with paler birds, and darker birds with darker birds.

In my experience, and in keeping with Megna’s observations at Protection Island, most of the large gulls in Puget Sound (over 90%) appear to be hybrids at the Glaucous-winged end of the spectrum. That is my default assumption when using eBird. For those not comfortable with that, eBird also offers the option of “Western/Glaucous-winged Gull,” meaning the bird could be either parent species or a hybrid between the two; it’s the catch-all option. Simply calling dozens or even hundreds of birds “Glaucous-winged Gulls” is not correct, though that practice is widespread. That said, my limited observations in the San Juan Islands and Victoria, BC suggest less Western influence up there.

Aug 15 – Mid-August is when the first juveniles descend from the rooftops and appear on the beaches. They are crisp, with uniform brown-gray scaled scapulars and coverts. Their primaries are not jet black as in Western, Herring, California, and most other dark-winged gulls; they are dark gray. The color tone of the wing tips varies, as does the darkness of the entire bird. Like Western, the face has a uniform sooty auricular (cheek) patch, and the bill is black, large, and with a bulbous tip (see the head shots above).

Sept 18 – A month later and they haven’t changed much. This one is a bit paler and browner, which could be a function of sun exposure as well. The scapular pattern varies a bit. Note the overall robust and stocky structure, with short primary extension past the tail (i.e. short wings).

Sept 18 – Here’s another example from the same day. This one has a nearly pale greater covert panel. California Gulls in the background.

Sept 24 – A delightfully coffee-cream version, very Thayer’s-like in appearance. However, the heavy bill, stocky structure, tiny eye on a large head, and short primaries rule out the more sleek and dainty Thayer’s.

Oct 4 – Changes are afoot. It’s October and the juveniles are already molting. The telltale sign are the molting scapulars (the back). (These are actually 1st alternate scaps which they will keep a long time.) Note that the upper half of the brown checkered feathers have been replaced by rather messy patterned ones with some gray tones. Also the head and body are molting in paler feathers, though the sooty cheek remains.

On the right-hand edge of the pic, you’ll see a second cycle bird with a pure white primary sticking out (what’s left of it). This old feather is being replaced by a fresh dark (nearly black) primary. More on that as we move thru the calendar.

Oct 11 – The molting back and scapulars are obvious here as a pale gray-blue patch on the bird’s back. This bird has neat oak-leaf patterned scapulars (very Herring like, though these are rather pale), but they will be molting out soon.

Some may be tempted to call this one Glaucous-winged, as it is paler, less sooty gray, overall, and the primaries are nearly concolorous to the body. Yet the overall darkness, the dark belly, and dark auriculars suggest Western influence.

That’s a 3rd cycle bird in the back. Note the primaries are obviously darker than the mantle.

Nov 1 – This darker bird has completely molted its back and scapulars.

Nov 1 – This bird is more delayed in its molt cycle; it still has a lot of checkered juvenile scapulars. All the birds in this pic appear to be Olympics.

Nov 12 – Some more late fall examples with molted back and scapulars. How dark or light they appear can change with light and the angle of the bird. These birds are definitely reflecting some sunlight.

June 8 – And now we’re in June. Gull identification in spring and summer is a mess because the birds get quite faded and tattered. Exhibit A in this is the late 1st cycle bird on the right. This bird is now about 10 months old and desperately in need of molting to replace these primaries, which have now faded to nearly white. But that does not make it a Glaucous-winged Gull (same for the adult behind it). The rest of the bird, particularly the face and belly, are still rather dark.

June 23 – Another formerly sooty 1st cycle bird that looks like it’s gone through the wash.

June 23 – As summer wears on, many Olympics will have tertials and primaries that fade to white. This happens even in some dark-winged gulls (e.g. Short-billed). This bird has many Glaucous-winged features, though the dark below and large bulbous bill suggest some Western influence.

July 3 – With birds like this, it becomes impossible to use plumage to separate them from pure Glaucous-winged. The heavy bill with a rather sharp hook and gonydeal bulge are a better fit for Olympic.

July 6 – Here’s another summer bird that is a bit darker, and thus more obviously an Olympic. The exposed primary has a dark shadow on it where it was once covered by another feather.

July 8 – More examples of faded summery Olympics. Note the heavy dark bills and dark bellies.

July 12 – At last, molt has begun. They molt their secondaries and primaries from the inside out. The fresh feathers here are more gray; the old feathers more brown. The old primaries – the last three or four feathers on each wing – are also warn to pin points. Note, on the left wing, the new dark-tipped primary starting to grown in. This is P5 (the 5th one in from the tip, which is P10).

July 12 – A close-up look at P5 coming in.

July 14 – Another individual molting in fresh gray primaries to replace the tattered faded ones.

July 25 – And another individual. Even this rather dark-faced bird had its primaries fade to white. The new one is dark gray.

July 27 – Finding molting birds like this in late summer is fun. This bird is in the process of changing from a white-winged gull (which some might confused with Glaucous) to a nearly black-winged gull (approaching Western)!

July 27 – Taken on the same day as above, this bird is much slower in its molt cycle.

July 30 – Another bird molting from white-winged to dark-winged.

Sept 27 – September again. This bird is now a year and a few months old. It still has one long thin old faded white primary left. It’s new 2nd cycle primaries are dark enough to clearly put this bird in the Olympic camp.

Oct 4 – Another individual with a single white primary left, but new dark gray ones coming it. The other birds are juvenile Olympics, just a few months old.

Oct 11 – And voila, a fully molted fresh 2nd cycle Olympic Gull, ready for the winter.

June 8 – Now approaching it’s third birthday, this late 2nd cycle bird is ready for molt again. Note the bill had changed from black to incorporate the classic school bus yellow of Western.

Sept 20 – A juvenile begs from its parent. You can tell this adult is an Olympic because it’s child is an Olympic (with rather dark primaries). The adult has some faded primaries which are being replaced by a feather with a much darker gray band.

Oct 26 – A fully molted adult with dark gray in the primary pattern.

Jan 17 – Some more adult mid-winter. While the front right bird has rather medium gray primaries, only a little darker than the mantle, note the bill lacks any dark mark (as seen in the bird to the left), which Glaucous-winged should show in winter. The clean yellow bill is a Western feature.

Feb 17 – Thanks to David Estroff for this photo from Port Townsend. This is not a pure Western Gull because: 1) the underside of P10 (the folded wingtip in the back) is not black, but a silvery gray, especially on the inside of the white mirror. In a pure Western, this would be nearly black. 2) the orbital ring is reddish. In pure Western, it should be mustard yellow. Pure Western Gulls are rare in Puget Sound. I usually encounter them after strong west winds in winter. The clean white head is because it’s coming into breeding plumage.

Apr 19 – This adult is in full breeding plumage. When breeding, the bill and legs get brighter and more colorful. Note the primaries are too dark for Glaucous-winged, but too light for Western.

California Gull

California Gulls are abundant in Puget Sound June thru October, when a wave of post-breeding migrants pulse through the region. Especially in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, they can outnumber all other species combined in late summer. They can be found at other times of the year, though in much smaller numbers.

June 29 – I love it when the first juv Calis show up – little checkered gems on the kelp-covered cobble. They are typically rather skittish, so hard to get close pics. This June bird is my earliest record; usually they show up around July 11. Olympic in the foreground.

July 16 – Here’s another one among the Heermann’s, compared to which they are only slightly larger.

July 25 – Juvenile California Gulls can be confusing because many have all black bills. This one is already turning pale at the base. Compared to Olympic, note the long primary projection past the tail, the jet black primaries (blacker than any Olympic), and more horizontal and sleek posture.

July 27 – Two different juvenile California Gulls, now with the more characteristic dirty pink bill with black tip.

Aug 9 – These birds can look like juvenile Herring (which aren’t expected for another two months), but note the solid dark inner primaries, lacking a pale inner primary window.

Aug 27 – Though they vary from dark to light, this is a very typical juvenile California Gull.

Aug 27 – Taken on the same day as the previous pic, this is what is colloquially called a “cinnamon morph,” rather pale juvs with warm brown tones and whitish underparts. Given the all black bill, it must be quite young as well. These are more regular in California than in the Pacific Northwest.

Sept 18 – Another gorgeous juv. The feathers can often have a cinnamon brown tone.

Sept 29 – California on the left; Olympic on the right. Both of these birds have started molting scapulars. They both have pink legs in first cycle, though Calif Gull legs are paler pink.

Sept 29 – Two California’s on the left; two Olympics on the right. All juveniles. Note the left California Gull still has an all-black bill. The California Gulls stand out by their smaller size, more horizontal backs, and long, black wingtips.

June 26 – We’re now through spring into summer. This bird is approaching its first birthday and is showing the classic tri-color pattern of relatively fresh gray scapulars, faded white coverts, and tattered primaries, now faded from black to brown.

July 6 – A similar late 1st cycle California Gull. Note the legs can turn rather blueish.

July 11 – This fly-by bird reveals it has begun molting its inner primaries – the fresh gray ones.

Aug 2 – This bird is probably a year more ahead, molting from 2nd to 3rd cycle. The legs are still rather bluish gray.

Dec 9 – This bird is a full adult, with black and red near the tip of the yellow bill. The blue legs will turn yellow by spring. Olympic back left; Short-billed Gulls back right.

July 15 – Finally, a full adult California Gull with yellow legs. Note the dark eye with red orbital ring and red gape (where the bill meets the face). The adult in the background with the messed up head feathers especially shows the red gape. Heermann’s back right. The black mark on the bill is much reduced when breeding.

Short-billed Gull

These petite beauties arrive in the fall to spend the winter, departing by May to breed in Alaska and Canada.

Oct 4 – The fresh juvs look like miniature Thayer’s Gulls, but are as dainty as fairies. Note the tiny thin bill and dove-like head with a relatively large eye. Also bantam chicken-like chest and very long tapered wings.

Nov 12 – Because this is a three-year gull, the 1st cycle birds quickly resemble 2nd cycle in large gulls, in that they have “adult gray” back and scapulars. This contrasts with the brown coverts.

Jan 9 – In flight they have a rather solid tail (unlike Ring-billed Gull).

Apr 25 – Here we are in spring. The brown coverts have faded to white, and head and body molt has also created a paler appearance.

July 14 – Occasionally, some late 1st cycle birds will over-summer. These often bleach to a nearly completely white, baffling birders. The bill seems longer than usual because the head feathers are molting.

Sept 18 – This is an adult just arrived from the north. Note the tiny unmarked yellow bill, somewhat unique in the gull world. California, Olympic, and Heermann’s tower over this tiny gull.

Jan 8 – Winter adults are beautiful in flight, with considerable white in the primary pattern: mirrors on P10 and P9, and a white “string of pearls” between the gray and black in Ps 4-8 (the Slaty-backed pattern). The exact pattern is variable.

Mar 25 – The amount of head and neck smudging in variable. Note that some birds will show a yellow eye.

Apr 25 – As spring gets on, the head markings resolve to a clean white head and the bill brightens as the breeding season approaches. This means they’re about to head north.

Heermann’s Gull

A striking and unique gull, nearly the entire world’s population emanates from tiny Isla Rasa in the Gulf of Mexico. After breeding, they migrate north. About 400 typically spend the summer and early fall around Port Townsend.

July 27 – The fresh juveniles are brown with mostly dark bills. The pale feather edges wear off quickly.

Aug 15 – This is a four-year gull. This photo features two brown juveniles in the back (molting their scapulars), a 2nd cycle front left, and an adult front right. Heermann’s Gulls have black legs at all ages.

Aug 26 – This 2nd cycle bird looks a lot like 1st cycle. It has a more orange bill.

June 29 – Breeding plumage adults are remarkable for their bright red bills, clean white heads, and smoky gray bodies.

Aug 26 – Adults in the August conspicuously molt their flight feathers and tails.

Oct 5 – Adults in complete basic plumage, with mottled dark heads.

Oct 4 – A small percentage of adults show “jaeger-morph” wing patterns, with variable amounts of white in the primary coverts. This adds to their jaeger habits of chasing other gulls.

Bonaparte’s Gull

Even smaller and daintier than Short-billed, Bonaparte’s Gulls are easy to identify and a joy to watch. I’ll leave it to other sources to help you pick out a Black-headed or Little Gull among them. Suffice it to say, the former is more larger, and the latter slightly smaller, than Bonaparte’s. These northern breeders are present throughout much of the year – except summer – with pulses during spring and fall migration. Hundreds can be found at Point No Point, often harassed by jaegers in the fall.

Aug 3 – A gorgeous freshly-arrived juvenile with the characteristic black year patch.

Aug 3 – Newly arrived adults, one still with an all-black head.

Aug 3 – An adult in flight, molting its primaries.

Nov 29 – An adult in full basic (winter) plumage. It appears to have an injury in the shoulder area.

Glaucous-winged Gull

Pure Glaucous-winged Gulls are challenging for me to find among the crowd of Olympics. At best, they are uncommon in winter and rare in summer, largely limited to a few over-summering subadults. That said, an influx in winter can match Olympic numbers at some roosts between Sequim and Neah Bay.

Oct 5 – Given the dusky auriculars and rather bulbous bill, this bird probably has some Western in it. Nevertheless, note the even pale tones throughout.

Oct 28 – There’s no question about this bird. The primaries are as pale as they come, as is the tail. The auriculars have no indications of a sooty wash. The coverts are intricately patterned. Note the scapulars are fully molted.

Nov 1 – Olympic on the left; Glaucous-winged on the right. At this date, fading is not an issue.

Nov 6 – This bird shows no auricular patch. The primaries are almost patterned as in Glaucous and Iceland. Note the bill, while heavy, is less blob-ended than Western or Olympic, with a shallower gonydeal angle. The tomium (upper edge) often begins a gentle curve about 2/3 of the way out, rather than a strong hook ¾ of the way out, as is typical in Western and Olympic.

Nov 7 – This bird shows a hint of subterminal arrowhead patterns in the primaries. Note the straight bill without a contrasting blob ending.

Nov 12 – Note the whitish head on this fall bird. The primaries on this one are quite pale. Olympic in foreground.

May 7 – By spring, Glaucous-winged Gulls can fade to nearly all white. Note the bill is beginning to pale.

May 12 – Another spring adult, though this one seems less faded. Again, the bill is paling and more straight than Olympic.

June 29 – As they molt coverts, Glaucous-winged Gulls often produce this striking pattern due to fresh dark coverts.

July 6 – Over-summering late 1st cycle birds often stand out in Puget Sound. Feathers with less melanin (paler feathers) are more prone to wear and fading than darker feathers.

July 14 – This bird could be confused for Glaucous, but a Glaucous would never have dark in the middle of the bill. Given the time of year, this bird is typical of an over-summering one-year-old Glaucous-winged Gull.

July 27 – Another over-summering 1st cycle Glaucous-winged, in desperate need of molt.

June 8 – We’re now a year later. This bird is late 2nd cycle, with a bill that is already acquiring yellow tones.

Jan 17 – A presumed pure adult Glaucous-winged Gull in mid-winter. Note the icy gray mantle and nearly matching primaries (though they are more slate gray than blue-gray), the purplish legs, the rather straight bill, and the straw yellow bill with the dark mark thru the red spot.

Ring-billed Gull

Ring-billed Gulls are rather rare to uncommon around Port Townsend. I only see them in small numbers (usually three or less) in late summer and fall. Apparently they are more common in the South Sound.

Aug 25 – Compared to California Gulls, the juveniles are smaller, whiter, and with brighter pink in the bill.

Nov 15 – In flight, 1st cycle birds have a tail with a messy band. California and Short-billed Gulls have much more solid brownish/blackish tails. Also note the very contrasting wing pattern with very pale window in the inner primaries.

Aug 19 – Adult Ring-billed Gulls have very pale mantles. They can be told from Short-billed Gull at a hundred yards by the lack of a contrasting white tertial crescent between the gray mantle and black primaries. The pale gray just fades into the black with only a small white fringe.

Thayer’s Iceland Gull

Gulling is traditionally best in the winter, when Arctic breeders such as Thayer’s Iceland Gull arrive. This is difficult in Port Townsend, as there are few high tide roosts nearby. In winter, there are rarely low tides during limited daylight hours. Thus, I usually only see a few Thayer’s, if any, on any given day. They are much more regular at the Elwha River Mouth, which also has suitable high tide roosts for midday viewing.

Nov 7 – Of the large four-year gulls, Thayer’s is amongst the smallest. Fresh juveniles resemble fresh Olympics with their checkering and coffee with cream tones, but their structure is very different. Note the thin bill and long primaries, almost always darker than the body and with pale edges.

Jan 9 – Thayer’s on the left; Olympic (or possibly Glaucous-winged) on the right. The main differences: Thayer’s is smaller, longer winged, has a much tinier bill, and generally retains its scaled juvenile scapulars through the winter; the Olympic has already molted them.

Sept 22 – From left to right: Heermann’s, Thayer’s, California, and Olympic. On the Thayer’s, note the dark eye, bright pink legs, and primary pattern with the pale underside of the far primary. This is actually P9 we are looking at. P10 is missing due to molt.

Oct 11 – Thayer’s often appear petite and squat, though they are slightly larger than a California Gull. Note the small bill. Many individuals show a gold eye.

Oct 11 – This is the same bird as above, showing off their unique primary pattern. P10 has a large terminal mirror (all white tip). P9 has a mirror that swirls open toward the inside of the wing.

Nov 15 – Here’s another view of the primary pattern, which produces a striped effect.

Feb 26 – How to pic a Thayer’s out of a flock of Olympic Gulls. It’s the small one in front. Note the jet black in the primary pattern, the thin bill, and the overall petite structure (it probably weighs 30% less than the Olympics). Note also the underside of the far primary on the folded wing is pale — this rules out Herring. The dark eye also rules out Herring (though some adult Thayer’s have somewhat pale eyes). The back left bird is a 2nd cycle Thayer’s — note the thin bill.

Herring Gull

Sept 18 – I see even fewer Herrings than Thayer’s, usually just a few each winter, unless I go to Elwha. Compared to Thayer’s and Olympic, note the black primaries and very dark tertials. The coverts are usually very checkered and contrasting. The bill can vary from all black to dirty pink with a dark tip.

Dec 2 – Here’s another Herring. Note the black primaries and contrasting pale head, a common feature.

Jan 30 – An adult in flight. They always have a very pale straw-colored eye, producing a fierce look. The mantle is pale icy blue. The typical primary pattern has only a single mirror on P10.

Western Gull

Sept 16 – Pure Western Gulls are rare in Puget Sound. I usually only see them in fall or winter after strong west winds. This juvenile shows a dark sooty face (similar to many Olympics) but also jet black primaries. Note also the more contrasting coverts, not the uniform muddy tones of Olympics. That’s a juvenile Olympic back right.

Sept 29 – This 3rd cycle Western shows a fairly dark mantle and jet black primaries.

July 27 – This summer adult is a classic Western: a clean white head (which they keep year round), a thick bulbous school bus yellow bill, a darkish mantle, and jet black in the primaries. Note also the yellow orbital ring. The eye varies from yellow to dark.

Herring x Glaucous-winged Gull (“Cook Inlet Gull”)

I only report a few of these each winter, usually at Elwha or Neah Bay. They are probably regular but rare in Puget Sound, but they are really a pain to pick out amongst all the Olympics!

Nov 6 – This one is easy to separate from Olympic – it has a pale version of the Herring Gull bill, pale with a black tip. The dark gray primaries rule out black-primaried gulls and imply either a Thayer’s or Gl-W hybrid. The molted scapulars, structure, and gray color tones rule out Thayer’s. Olympic in the background.

Nov 12 – A likely Cook Inlet, with a straighter and more paling bill than found on Olympic. Cook Inlets often retain juvenile scapulars later in the winter, as this one has. Note also the longer-winged structure.

Jan 8 – Another potential Cook Inlet with unmolted scaps (in January!) and a longer-winged structure than Olympic. The more squared off and contrasting pale head also suggests Herring influence. 2nd cycle Olympic in the background.

Glaucous Gull

Large and white, these are rare winter visitors.

Nov 9 – Most Glaucous Gulls in Washington are 1st cycle birds, like this one. I took this on the beach at Ocean Park. It is accompanied by adult Ring-billed and Western Gulls. The bill is always pink with a well-demarcated black tip. Glaucous-winged never approaches this at any age. Note the bill is also straight and not blob-ended.

Rarities: These species, listed roughly in order of probability, occur less than annually: Franklin’s Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Black-legged Kittiwake, Black-headed Gull, Little Gull, Slaty-backed Gull, Black-tailed Gull, Ross’s Gull

Probability by season

It always helps to know which gull species are around at any one time during the year. eBird data for gulls in Puget Sound is of little use due to widespread misidentifications. This graph is based on my personal eBird data from Pt Wilson and Pt Hudson near Port Townsend. Frequency may vary around the Sound and at other gull roosts. For example, Ring-billed Gull is quite regular in the South Sound earlier in the year, and Thayer’s and Herring are regular at the Elwha River Mouth in winter.