The boom: Life in the fast lane

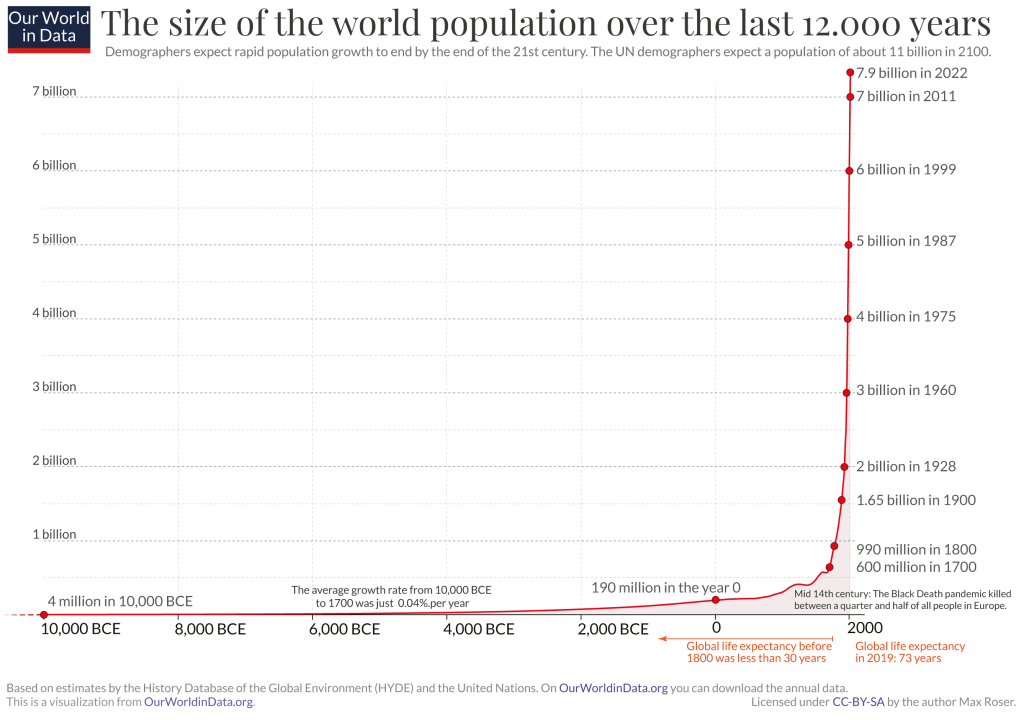

The basic facts are clear. Homo sapiens cruised along for most of our 200,000 years with a small population, probably less than a hundred thousand. Then something happened. We expanded, emigrating out of Africa and across the globe. About 10,000 years ago, when our population was around four million, we developed agriculture. Cities and large organized societies – and money and writing – came along later. The human population really took off. This growth became exponential. Homo sapiens passed 1 billion around 1800, 2 billion in 1928, and 5 billion in 1987. Our impact on the earth has been so dramatic that geologists have coined a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. When I was a child, I was told there were more humans alive on the earth than had ever existed in the history of the species. If that’s not the definition of a population boom, I don’t know what is.

Today we’re just over 8 billion, but we’ve passed an inflection point. The rate of increase is decreasing, from 2% per year in the 1960s to less than 1% now. The S-curve is forming. The top of the curve is bending, ultimately to be replaced by a decline. Demographers predict that human population will peak in 2064 at about 9.7 billion. After that, the decrease may be equally precipitous.

In most “developed” nations, the fertility rate (the average number of children that a woman has in her lifetime) has fallen below 1.6. The fertility rate is 1.23 in Spain, 1.24 in Italy, 1.34 in Japan, 1.44 in Austria, 1.53 in Germany, 1.56 in the UK, and 1.64 in the United States. It takes a fertility rate of at least 2.0 to maintain a steady population (not counting immigration). The countries with the highest fertility rates, over 4.0, are in sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan, though even those are declining sharply. Every nation in the world may have a shrinking population by 2100.

The bust: It’s the end of the world as we know it

The worldwide average fertility rate is predicted to be 1.7 by 2100. That implies a population decline of about 9% each generation (about 25 years). This, in turn, implies a 50% decline in total population within 200 years, and a 90% decline, back below one billion, in 600 years. That’s basic math. That’s a freefall, a massive shrinking of human society.

This kind of population collapse is not unheard of in the natural world. Many species, from lemmings to locusts to crabs to passenger pigeons, are known as boom-bust species, with wild swings in their populations. Some research suggests that wild swings in animal populations may be the norm.

The bust – the fall, the decline, the collapse – is often driven by hitting the carrying capacity of the resources they depend on. Simply put, the species runs out of habitat or runs out of food. Life, literally, becomes too difficult. Animals may die or simply fail to reproduce.

When the world is running down, you make the best of what’s still around

What is it like to be an individual living during a bust cycle? Apart from a few perturbations in history (see Collapse by Jared Diamond), it’s a world that humans are unaccustomed to.

The economy will be shrinking, both supply and demand. The stock market will fall daily, for most businesses will be in decline. Stores will be closing, never to re-open.

By definition, deaths will outnumber births, which means the demographic age mix will be decidedly older. By definition, many won’t have children to look after them. They will need to rely on paid caregivers, which will be in short supply.

We have a hint of that economic upheaval now, with supply shortages as we emerge from the Covid pandemic. Recent research suggests that half the lost workers in the US today are actually a result of Trump’s crackdowns on legal immigration. It is immigrants, after all, who make up the difference in the US’s low fertility rate. Those labor shortages, and the resulting supply chain problems and inflation, are caused by more people aging out of the labor force than aging in. This can only be mitigated by immigration.

When immigrants are no longer available, how does a nation manage a declining economy, a permanent recession? Public services – police, fire, water, electricity – will be difficult to provide everywhere. Service will be terminated in rural areas. Outlying areas and small towns will be abandoned as people seek services (primarily medical at first) in larger cities. Schools, healthcare clinics, stores, and homes will crumble as the population concentrates into remaining urban centers. All production, especially agriculture, will need to efficient, relying less and less on labor. With a lack of private investment, will government need to play a stronger role to guarantee the provision of goods and services?

What does this mean for culture? So many of the values, customs, and social rules of the past ordered growing societies, supporting the family, state, and nation. In a declining society, the center, the things we hold dear, does not hold. Things fall apart. Sure, one can strive for personal peace and meaning, but family lines will end. There are no “greatest” generations building infrastructure for the future.

Will there be a collective future to aspire to? Perhaps divisions of the past – gender, race, nationality – will lose meaning in the face of a shared human condition. On the other hand, we already see those tensions exacerbated as people glimpse the future, desperate to cling to the past.

Perhaps a shrinking economy can be managed. Perhaps there is a soft landing to societal collapse, to shrinking our footprint to a new steady-state in a sustainable harmony with nature.

We don’t know yet. We’re still on the crest of the wave, the top of the curve, enjoying the best of times. It’s our kids and grandkids and great grandkids who will come up against that carrying capacity. And that’s exactly why many are choosing not to have kids. Others don’t have kids because they have other economic or personal opportunities, thanks to our societal successes. But even in this decision, they feel no imperative to have kids. Indeed, the imperative is to reduce our impact on the earth. It looks as if that will happen. For the earth, a short-lived Anthropocene will no doubt be a good thing. For the people living during the collapse, perhaps not.