I realize a lot of people are pretty burnt out on this issue, myself included. But, in the face of persistent efforts by detractors to petition the AOS for a case-by-case approach to bird name changes, some important backstory is necessary.

Here goes: The controversy over changing English bird names began at least 24 years ago. The current proposal, to change all the eponymous English names, is connected to that history. The process that changed the name of McCown’s Longspur, while it succeeded in creating a new name for that one species, essentially killed the case-by-case approach.

I was a member of the Ad Hoc English Bird Names Committee, but I only reached the conclusions above after our task was done. In the fall of 2023, we made recommendations to the American Ornithologists Society (AOS) regarding changing “harmful and exclusionary English bird names.” You can read our recommendations, along with all the justifications, in detail at this link.

Now I’m adding more to the story. After our committee disbanded, I did a personal deep dive – one that I probably should have done from the start – into the backstory of this debate, to understand just where our Ad Hoc Committee fit in this history.

Here is what I learned.

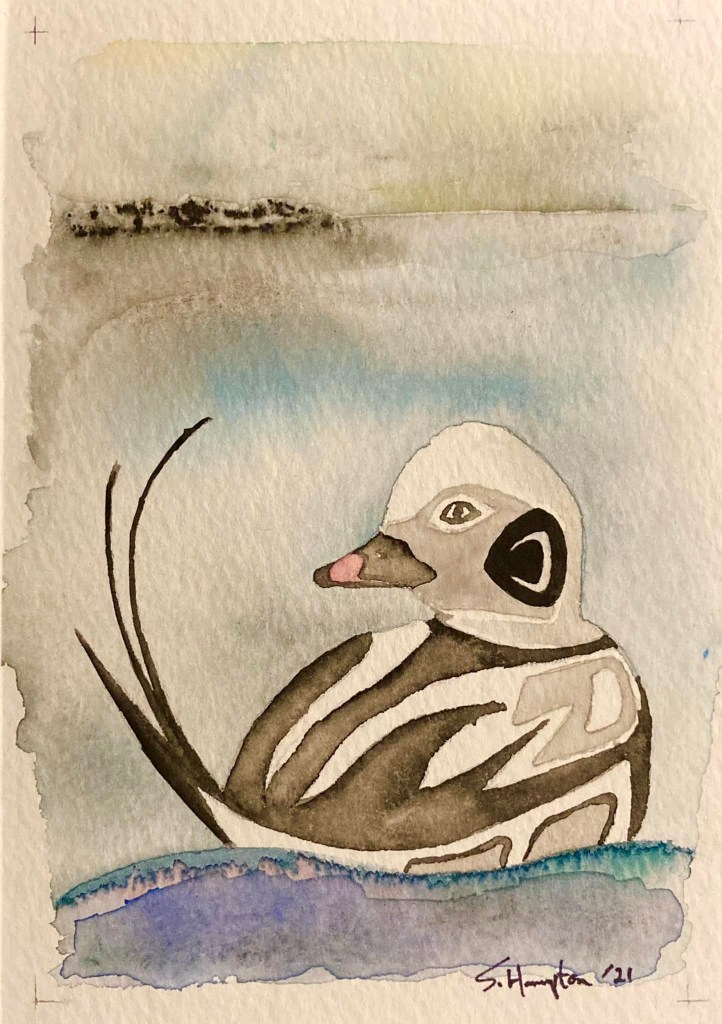

2000: The duck

There has been a simmering conflict between AOS leadership and the North American Checklist Committee (NACC) that goes back at least to the Long-tailed Duck proposal in 2000. The South American Checklist Committee (SACC) is also part of the story, but I’ll focus mostly on the NACC.

In 2000, a proposal came before the NACC to change a bird name not because of some refinement in taxonomical understanding, but for a cultural or social reason. The bird was the Oldsqu*w, a name that incorporates a painful slur about Native women. (The word is derived from an Algonquin word for woman. Over time, it was appropriated by European men, given new meaning, and spread by cavalry and pioneer wagons across the continent. It often appeared in first-hand accounts of impregnated captive Native women held in US forts. This term is especially insulting and dismissive in Indigenous cultures, where women traditionally held, and still hold, positions of much greater influence and respect than their European counterparts.)

The proposal to change the name of the duck came from the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska, where coordination with Alaska Natives is a necessity and an obligation. After what must have been considerable internal debate, the NACC agreed to change the name to Long-tailed Duck, begrudgingly. If you read their explanation, they went out of their way to say they were “not doing this for reasons of political correctness,” but only to bring the name into alignment with English-speaking counterparts in Europe, who already called it the Long-tailed Duck. They didn’t mention the partnership issues in Alaska at all. Their inflammatory comment was a shot across the bow. They were making clear they were pressured into the name change, and resented it, and so contrived an alternative justification for it.

The Supreme Court of birds

The most surprising thing I learned while on the Ad Hoc Committee is that the NACC has changed little since 2000. The majority of the members on the committee back then are still on it today. That’s because they have no term limits. When there is a vacancy, such as when someone dies, the existing members choose the replacement. Thus, they are an island unto themselves, with no external appointments and little oversight from the parent organization. Structurally, they are more protected than the Supreme Court – and have less turnover.

In such a context, of course, a committee can act with a sense of entitlement and impunity. I was shocked when a few of their members criticized the mission of our Ad Hoc Committee publicly. As a former high-level manager with the California Department of Fish and Game, we would never permit one arm to attack the other in public. These attacks cast a shadow over our meetings, as if the NACC carried more weight than the millions of other bird name users. While I acknowledge there was an organizational awkwardness in that the Ad Hoc Committee was tasked with making recommendations regarding part of another committee’s purview (English bird names), there were appropriate internal channels for communication. Most significantly, a member of the NACC was also a member on our committee (with whom we always had respectful and professional discussions).

2011: The dove

Eleven years later, the NACC considered another proposal to change just the English name of a species. Remarkably, the proposal came from within the committee, from Van Remsen, one of its most preeminent ornithologists. Having been on the committee since (so long I can’t figure out when), he was on it during the Long-tailed Duck discussion in 2000.

Remsen immediately recognized that considering a change for social reasons was not the norm. He opened his proposal, entitled “Change English name of Columbina inca from Inca Dove to Aztec Dove,” this way: “I‘m serious. At least I want us to think about this one. As you know, I‘m strongly opposed to meddling with English names, and I regard stability as paramount. And as far as I know, this species has been called “Inca Dove” forever. But in this case, it‘s not just a bad name, but also a completely misleading, nonsensical, embarrassing name that should not be perpetuated – I think it reflects badly on us as a committee…. Its perpetuation only confirms to Latin Americans how ignorant most Americans are of anything beyond our borders.”

His primary issue, however, was not political correctness, but factual incorrectness. The dove’s name was “misleading,” Remsen argued. His colleagues rejected the proposal 5-4 (with presumably Remsen, as the author of the proposal, abstaining). Many names are misleading, they argued. One dissenter summarized the prevailing view, “The name doesn’t reflect our ignorance, but Lesson’s. This vote is for stability.” This illustrated two key themes in NACC jurisprudence: 1) mistakes of the past are allowed to stand, no matter how offensive; and 2) stability, critical for taxonomy, will be applied to English names as well as scientific names.

Another dissenting member stated, “I was a reluctant yes on this, but then canvassed some respected birders and was met with complete non enthusiasm. English name changes always invite acrimony and I fear that result here.” This comment reveals two more characteristics about the NACC. Despite their credentials in taxonomy, they are notably sloppy when it comes to social science, much less public relations. The survey pool of “respected birders” were likely older white males, the demographic most likely to be described that way, and presumably acquaintances. At the very least, the dissenter does not go out of their way to say they were Latinos, either from Mexico or South America, or that the sample was representative in any way. Second, the dissenter fears acrimony, and thus gives high priority to how the users of English bird names, mostly white Americans, will view a name change, even if the name involves a bird which lives primarily south of the US, or involves a moral issue affecting non-white people. In short, they do not want to offend a certain subset of bird name users.

Their comments paint a picture of a committee unprepared for public relations, yet cavalierly unafraid of developing opinions on issues outside their field of expertise.

2011: The honeycreeper

The same year the Inca Dove proposal narrowly failed, the NACC considered one other proposal to change just the English name of a bird. The proposal came from Hanna Mounce, a PhD ornithology student involved in protecting the critically endangered Maui Parrotbill.

The use of Hawaiian names for Hawaii’s birds is common – Elepaio, Apapane, Iwii, Amakihi. But the indigenous name for this bird had been lost from local memory. It was thought to be extinct after 1890. The English name was given after it was rediscovered in 1950. Parrotbill is misleading, to borrow Remsen’s word for the non-Aztec Inca Dove. Parrotbills are an entirely separate family of birds, which includes babblers and the Wrentit. The Maui Parrotbill is actually a Hawaiian honeycreeper, which are part of the finch family.

Of the 21 Hawaiian honeycreepers, only two carry official English monikers, the Maui Parrotbill being one of them. Seeking community support for preservation actions, Hawaiians – specifically, the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project and the Hawaiian Lexicon Committee – initiated a re-naming process to replace the name lost to colonization. In 2010, the name Kiwikiu was selected. Like many indigenous names, the name included a reference to its appearance, with double-meanings for its habits and habitat. A re-naming ceremony was held on the slopes of Haleakalā, where the last few hundred Kiwikiu still cling to existence. In the name change proposal, it was noted that Kiwikiu “is now widely used in avian conservation in Hawaii.”

Compared to the Aztec Dove proposal, the Kiwikiu had a lot more going for it. First, it addressed a taxonomically misleading name, and second, it had a groundswell of local support driven by conservation concerns to save one of the world’s most critically-endangered species.

The NACC, however, was unmoved. They rejected the proposal 10 to 0. In reporting their decisions, the NACC publishes their votes and comments online, redacting the names of the committee members. Thus, all the reader sees is a vote and their rationale. In this case, they also saw unprofessional disrespect and racial bigotry. The comments included: “NO. The last thing we need is yet another ridiculous Hawaiian language name.” Another said the new name was “contrived, unfamiliar, and unpronounceable.” As for “parrotbill” referring to a completely unrelated family of birds, this was dismissed as “at most a minor issue.” One committee member conceded that “the name Maui Parrotbill is a lousy one” but added “I’d leave as is…. Has it ever been called a Kiwikiu by anyone?” Apparently, anyone did not include the Hawaiians involved it its protection.

Among the NACC, Remsen’s advocacy garnered four votes for the dove, but the Hawaiian bird conservation community could not sway a single one.

2018: The jay

What would happen if a bunch of white people, with close ties to the NACC, wanted to change an English name for social reasons? We found out in 2018 with the Gray Jay. The proposal came from seven Canadians, all academic ornithologists, one who was a member of the NACC, and another the president of the Society of Canadian Ornithologists. Where the honeycreeper was represented by an unknown soldier, the jay had inside connections and a prestigious army.

The Gray Jay, they argued, should be renamed the Canada Jay for several reasons. First, it was called that before a cascade of name changes in 1957. Second, they were considering it for their national bird. And third, the spelling of “gray” was American, not Canadian, and therefore not acceptable as a national bird. In their justifications, they included a possible threat to the NACC’s authority: the Canadian government could justifiably choose the Gray Jay as their national bird, but rename it, at least for official government purposes, the Canada Jay, just as Hawaiians were already doing with the Kiwikiu.

With intimate knowledge of the NACC’s policies and procedures, they targeted a procedural mistake in 1957. They argued that the name should have reverted to the old historic name of Canada Jay at that time.

The NACC embraced this argument by a vote of 9 to 1. Astoundingly, four of the “yes” votes were without comment. Those who commented embraced the technical argument that the name should have, following their rules, resorted to Canada Jay in 1957. Several mentioned that they had no real concern that the jay occurs well south of the border. And several mentioned the potential of it being a candidate for national bird. Finally, one summarized their rationale with let’s “be cordial to the Canadians.”

The lone detractor was curmudgeonly unbiased. They dismissed the importance of the national bird campaign and argued that 1957 was “the starting point for English names for birds,” so Gray Jay should remain.

While the cultural concerns of Native Americans regarding the Oldsqu*w and Native Hawaiians regarding the parrotbill were explicitly rejected, the Canadians were successful, an illustration of how white privilege and structural racism works. They rely on bylaws and policies. Social justifications are downplayed. Instead, they use inside connections to navigate the bureaucracy, while marginalized people founder on the rocks of regulatory minutia.

2019: The longspur

A year later, Robert Driver, a young academic ornithologist, submitted a proposal to change the name of McCown’s Longspur. John P. McCown, the proposal explained, had been a prominent officer in the Confederate Army. The proposal cited the AOS’s 2015 diversity statement, arguing, “All races and ethnicities should be able to conduct future research on any bird without feeling excluded, uncomfortable, or shame when they hear or say the name of the bird. This longspur is named after a man who fought for years to maintain the right to keep slaves, and also fought against multiple Native tribes.”

The NACC would no doubt have been cognizant that similar arguments could be made about Audubon and Bachman, both proponents of slavery, not to mention Clark, Scott, Abert, Couch, and others, who were active participants in ethnic cleansing, as well as Townsend, who dug up Native skulls for Sameul Mortensen’s Crania Americana.

Diversity arguments notwithstanding, the NACC rejected the proposal 7 to 1, with one abstention. Reading their rationale, most of the committee members embarked on a seemingly apples-to-oranges comparison of McCown’s early days collecting birds and his later life as a Confederate officer, ruling that the significance of the former outweighed the transgressions of the latter. In the words of one, McCown “made important contributions to ornithology and that his remaining life (from what we know right now) did not prove so morally corrupt that we should cease to recognize his name in association with this bird.”

In short, rather than discuss the message that these names send to bird name users today, they simply put the long-dead McCown on trial in a weird kangaroo court that compared his ornithology to his offensiveness.

This is a rather bold endeavor for an all-white committee. If any of them sought assistance in making this evaluation from Black or Native users of bird names, they do not mention it. They do state they solicited feedback from the AOS Committee on Diversity and Inclusion, though no details are provided.

Several mentioned “judging historical figures by current moral standards is problematic.” At issue were slavery and ethnic cleansing. Both were extremely controversial then. A war was fought over one. The Indian Removal Act was quite possibly the most debated piece of legislation ever considered by Congress. And that’s just among white people. Blacks generally opposed slavery in the South, and Natives opposed their ethnic cleansing. These “moral standards” have not changed. What has changed are the people at the table today.

By implying that slavery and ethnic cleansing were not considered offensive or unethical then, they offer an olive branch to past slavers and Indian killers. They seemed to defend McCown as if they were defending one of their own, a fellow ornithologist. They failed to even discuss the larger question of what message these names send to Natives and Blacks who are part of the birding and ornithology world today.

2020: Revised guidelines

In their McCown “ruling,” many of the committee members, including the sole voter to change the name, and the abstainer, expressed discomfort about a group of taxonomists embarking on this decidedly non-ornithological task without a clear guiding policy. In the words of the abstainer, the committee needs “a general policy about issues of this type so that we are not responding to them as one-offs.”

Anticipating more proposals of this nature, the committee revised their Guidelines for English Bird Names. It was released on June 3, nine days after the killing of George Floyd. It included Section D: Special Considerations. If the goal was to add clarity to the morass they encountered during the 2019 McCown trial, the new guidelines made little progress.

First, they opened with this: “The NACC recognizes that some eponyms refer to individuals or cultures who held beliefs or engaged in actions that would be considered offensive or unethical by present-day standards.” Again, this centers the white experience and ignores the historic ethical standards of Blacks and Natives.

The second disturbing element of this introduction is that the NACC seemed to contemplate putting entire cultures on trial. It would be difficult to grasp what they meant by “or cultures,” except that at least one member of the NACC has suggested, in recent public retorts about changing eponyms, that Aztec is a potentially inappropriate name. This member repeated white stereotypes about Aztecs – killing prisoners via brutal methods – and applied these actions to an entire people and culture, an argument that reeks of double standards and tropes about Native savages.

(I consider Aztec, Mayan, Chaco, Chihuahuan, Urubamba, and Ayacucho in the same way as American, Japanese, Chilean, Mexican, Ethiopian, and California – these names use human societies as geographic descriptors, not as an honorific.)

The new guidelines continued to use the framework of a criminal trial, moving into details as if they were a code of law: “By itself, affiliation with a now-discredited historical movement or group is likely not sufficient for the NACC to change a long-established eponym. In contrast, the active engagement of the eponymic namesake in reprehensible events could serve as grounds for changing even long-established eponyms, especially if these actions were associated with the individual’s ornithological career.” Just being a member of a bad group is not a crime; you must actively participate.

They also acknowledged that some names could become derogatory or offensive over time, when at first they were not, and that the new guidelines would have allowed the name of Oldsqu*w to be changed based on that alone. All questionable names, however, would be subject to the same apples to oranges comparison: “The committee will consider the degree and scope of offensiveness under present-day social standards as part of its deliberations.” The “scope of offensiveness” will be compared to their contributions to ornithology. Specifically, eponyms that “have a tighter historical and ornithological affiliation” will have “a higher level of merit for retention.” It is difficult to see how this would work: minus two points for slavery but plus one for each new specimen collected?

Yet, this is where we are: the case-by-case approach rests on a committee – primarily white and male, with no term limits or external review – essentially putting historical figures on trial, comparing a name’s “scope of offensiveness” to the historical person’s “level of merit.” At no point do the new guidelines contemplate seeking input from a wider audience.

2020: The honeycreeper revisited

As these guidelines were published, the nation was embroiled in the threat of police violence against Christian Cooper and the murder of George Floyd. Birders and ornithologists who felt excluded from the largely white cis male confines of birding, ornithology, and the environmental movement in general, created multiple affinity groups where women, LGBTQ ornithologists, and Black birders could find a home. In this context, the AOS was forced into a deeper review of its actions, particularly the actions of the NACC.

In August 2020, the AOS issued a “profound apology” for the NACC’s “offensive and culturally insensitive comments” regarding the Kiwikiu proposal nine years earlier. If you pull up the NACC’s minutes online today, you will see that the comments of fully six of its ten members required redactions. A seventh had simply commented, “I agree with all the others for the reasons they already stated.” The AOS’s apology added an open threat to the NACC: the comments violated their 2015 Statement on Ethics and that, had their comments been made after that date, the members of the NACC “would be referred to the AOS Ethics Committee.”

There was no formal apology from the NACC. That the name Maui Parrotbill remains unchanged to this day illustrates the power balance between that committee and its parent organization.

2020: The longspur revisited

As the Kiwikiu controversy was simmering, somehow, behind the scenes, the longspur proposal was resurrected, revised, and resubmitted. Officially, it came from Terry Chesser, a member of the NACC, as well as Driver, the original author in 2019. Packaged in Supplemental Proposal Set 2020-S, it was the only member of the set. Clearly it was an emergency measure. It was also carefully constructed to achieve the desired result – changing the name of McCown’s Longspur – while simultaneously building a narrow jurisprudence that would avoid opening the door to similar proposals.

Again, the NACC adopted the approach of putting McCown on trial. The proposal reads like a criminal indictment, focusing on McCown’s resignation as a US Army Captain in order to join the newly-founded Confederate States Army in 1861. He was not known to keep slaves. Instead, they focused on a Confederate flag he kept in his home as proof of motive.

The proposal glosses over his first 21 years in the US Army with this: “He led campaigns against Native tribes along the Canadian border before being moved to Texas to serve in the Mexican War. He later fought the Seminoles in Florida and served several other positions before the onset of the Civil War.” That’s it. In fact, McCown was involved in the ethnic cleansing of the Seminole, Ute, Shoshone, Cheyenne, Lakota, and Comanche, from Florida to Utah to the Dakotas. Of people honored with bird names, perhaps only Clark (of Lewis & Clark) was involved in more Indian killing. When McCown collected the longspur in 1851 in south Texas, the Comanche Empire was actively pushing the Euro-American frontier backwards.

Instead, the proposal goes into great detail about his switch from the US to the Confederate Army, as well as the significant role he played in the Confederate Army. Essentially, they put McCown on trial for treason. When he was killing Indians, he was following orders of the United States. When he was defending slavery, he was a rebel.

The NACC grabbed this branch, voting 11-0 to change the name. In their comments, nine of the eleven highlighted his treason. In the words of one, “McCown resigned his commission before secession, indicating he was “in on” the movement to retain slavery, and then spent the Civil War killing soldiers in the United States Army, in which he was trained, in order to maintain a slave state. That puts McCown, in my opinion, in a completely different zone from all the other eponymous ornithologists of the era who were largely cultural products of their era.”

That last line preemptively exonerates all the Indian killers, even though their behavior was considered abhorrent by all the Natives and half the whites of their era. In the weighing of apples and oranges, there will be no point deductions for ethnic cleansing, not even for McCown. Given the increasingly prominent role that Native nations are playing in wildlife conservation (motivating both the Long-tailed Duck and Kiwikiu proposals), this approach is insensitive and potentially reckless.

Another wrote: “My original NO vote was based on McCown’s rebuke of the Confederacy and the time-honored principle of not judging past people by current standards. But then we learned more about McCown, and I read a fair amount on the history of slavery… it was clear that slavery was NOT regarded as normal, but instead abhorrent, by the vast majority of Western Civilization…. Thus, it was clear that by official cultural standards at the time of the Civil War, the beyond-odious practice of slavery was not considered “normal” for the era. The USA was an outlier, despite widespread, strong abolitionist sentiment dating into the previous century.”

The white ethnocentrism here is thick. One would think that a civil war would be evidence enough that the “official cultural standards at the time” were hotly contested. Instead, this taxonomist did personal research to confirm that slavey was indeed abhorrent, using white sensibilities as a guide. They did not research the views of Black voices from the US to see if they considered slavery abhorrent. It is apparent that “official cultural standards” meant “what most white people thought,” or even, “what a white government allowed.”

Only two members did not mention McCown’s allegiance to the Confederacy. This is because they did not put McCown on trial. Instead, they took it as a given that the name was problematic and focused on a larger goal. One stated that “promoting anti-racism within AOS should be a top priority.” The other, who had also been sole Yes vote in 2019, said, “I see changing this name as promoting a more inclusive AOS and birding community.”

In changing the name to Thick-billed Longspur, the NACC put McCown on trial, found him guilty, but did it in a way that no one else could ever be guilty. In the future, the case-by-case approach, for the most part, would be a dead end.

In recent public statements, some members of the NACC have affirmed this, saying they could “defend” Scott and Townsend. Indeed, they explained exactly how above.

What happened next

Within a year, the NACC received similar proposals to change the names of Scott’s Oriole and Flesh-footed Shearwater. A research group was writing papers – published by the AOS in their journal, Ornithology – where they refused to use the English name, Townsend’s Warbler. In South America, eBird/Cornell/Clements refused to go along with the SACC regarding honorifics for two new antpittas. Bird Names for Birds formed and petitioned for more name changes. It seemed a flood of similar proposals was inevitable, which would inundate the NACC with non-taxonomic duties. It was in this context – and with that historical backstory – that the AOS put a freeze on such proposals and began the process which led to the creation of the Ad Hoc Committee.

One could argue that, while the NACC may not be the right body to embark on a case-by-case approach regarding English bird names, perhaps a separate, more diverse, more socially-focused committee, could. The AOS seemed to think along these lines as well. That’s why they created us, the Ad Hoc Committee. In terms of diversity, we were at the opposite end of the spectrum from the NACC. Of our 11 people, we had ornithologists, birders, government resource managers, people from Canada, the US, Chile, Colombia, and Trinidad & Tobago, men, women, Asian, Latino, Black, Native, as well as current members of the NACC, SACC, and the AOS Council.

We spent our first six months trying to figure out how a case-by-case approach might work. We eventually realized that a universally-accepted “moral standard” did not exist, that we are a land of many narratives. Clark “opened the land” for white pioneers, and was also among the first US officials to use the term “extermination” with respect to Native Americans. One person’s hero is another’s enemy. Combined with a host of other problems with eponyms – their dismissive use of first names for women, their lack of information about the bird, and the personal property implied by the possessive ‘s’ – it was no surprise that our committee ultimately recommended changing them all.

Actually, I was surprised at the time. I never expected us to reach that conclusion. Looking back, however, I’m now convinced that any committee, focused on diversity and inclusion, would end up in the same place. And that a case-by-case approach would go nowhere.

Stebe,great article, informative and fun. I couldn’t stop reading. Belize was excellent. Jacamar, spectacled owl, king vultures, Central American pygmy owl close up, motmot, trogons, squirrel cuckoo, 18 wood warbler spp. We beat the heat (by various tricks) and Marianne loved that it was so green and lush. Michael

LikeLike

Very informative summary! Thank you!

LikeLike

Great deep dive into this issue. The background is worse than I knew!

LikeLike

Thanks for this thoughtful recap. I hadn’t realize that that NACC was more stable than many bird names…

LikeLike

LOL – brilliant take!

LikeLike