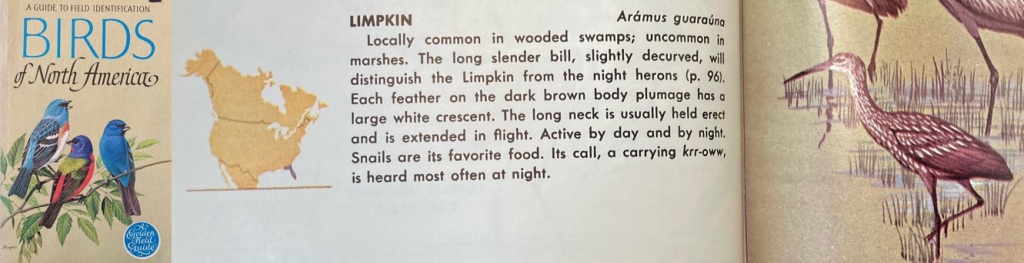

When this field guide was published in 1966, it was clear from the range map that, if I wanted to see a Limpkin in the US, I had to go to Florida.

Growing up as a kid birder in the 1970s, this was one of my first field guides. I did not see my first Limpkin until decades later, in 2005. At that time, this freshwater snail and mussel specialist was still largely a Florida bird, with only a scattering of records north of their usual range.

Between 1956 and 2015, eBird shows only 18 Limpkin sightings north of Charleston, South Carolina, though presumably some historical records have not been entered. Suffice it to say, a Limpkin in this region was a rarity. There were no Gulf Coast records in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, or Alabama, and only a few in the Florida panhandle west of the Tallahassee area.

Suddenly, all this changed. 2019 saw records from Illinois, Ohio, Virginia, and coastal Louisiana, in addition to dozens of records from Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina. 2020 and 2021 added a scattering of records from Texas to Minnesota(!) to Maryland.

In 2022, they simply exploded, with first state records across much of the continent. 2023 looks like it is picking up where last year left off.

This kind of rapid range expansion is typically seen in invasive species who are introduced into a new ecosystem. They either die out or explode. The Limpkin invasion, however, is not because they have just arrived in Florida — they are a native species — but because the ecosystem north of Florida has been transformed by a warming climate. It is as if they have landed on a new continent. They are following food — an invasive apple snail, as well as freshwater mussels.

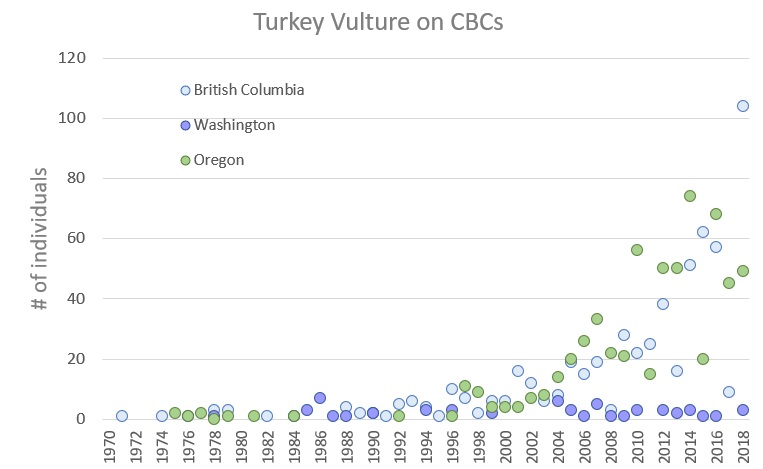

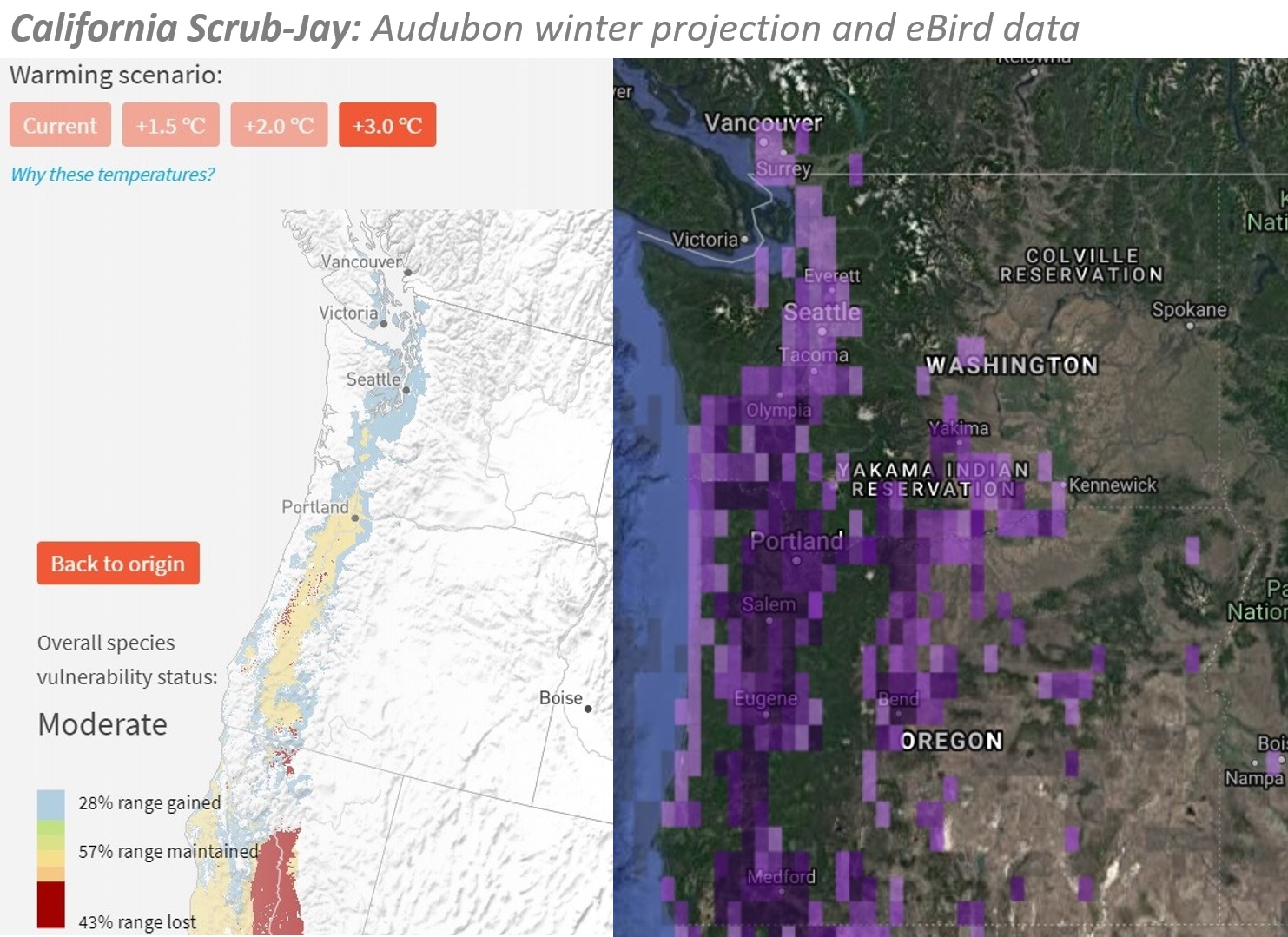

This kind of poleward range expansion is predicted with climate change and has already been documented in hundreds of species. See, for example, my posts here:

- eBird Trends maps reveal dramatic northward range shifts in Eastern species

- The invasion of the Pacific Northwest: California’s birds expand north with warmer winters

- Heading south for the winter, more birds are choosing the Pacific Northwest

And these scientific papers:

- Amano et al. 2020. Responses of global waterbird populations to climate change vary with latitude. 10: 959-964.Chen et al. 2011. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333 (6045): 1024-1026.

- Devictor et al 2008. Birds are tracking climate warming, but not fast enough. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 2743–2748.

- Hitch and Leberg. 2007. Breeding distributions of North American bird species moving north as a result of climate change. Conservation Biology 21(2): 534-9.

- Langham et al 2015. Conservation status of North American birds in the face of future climate change. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0135350.

- La Sorte, F.A., and F.R. Thompson III. 2007. Poleward shifts in winter ranges of North American birds. Ecology 88(7):1803–1812.

- La Sorte FA and Jetz W. 2012. Tracking of climatic niche boundaries under recent climate change. J Anim Ecol. 81(4): 914-25.

- Prince, K. and B. Zuckerberg. 2015. Climate change in our backyards: the reshuffling of North America’s winter bird communities. Global Change Biology 21(2): 572-585.

- Stephens et al 2016. Consistent response of bird populations to climate change on two continents. Science 352(6281): 84-7.

- Virkkala, R. and A. Lehikoinen 2014. Patterns of climate-induced density shifts of species: poleward shifts faster in northern boreal birds than in southern birds. Global Change Biology 20: 2995–3003.

[A more complete list of academic papers about birds and climate change, with highlighted abstracts, is available in the Documents section of the Birds and Climate Change Facebook group.]

Like many birds with expanding ranges, Limpkins have been slowly recovering for decades from historic habitat impacts. There are historic records (from the 1800s) from Georgia, which they did not occupy again meaningfully until 1994. Likewise, expansion into the Florida panhandle was not until the late 1980s. This fits the typical climate change pattern, with ecosystem changes beginning in the mid to late 1980s. Range expansions, however, can be variable, with different species crossing ecological and climatological thresholds at different times.

Like most of the species shifting their ranges, Limpkins are generally non-migratory, though may have some seasonal movements based on water levels and foraging conditions. Most the recent northern records have been in summer. It is not known if these birds return south in fall, or die, not being able to withstand the winter. That said, they are undoubtedly establishing year-round presence in southern Louisiana (where the first state record was in 2018), and likely from Texas to South Carolina. There are recent winter records from Iowa, Ohio, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Virginia.

The Limpkin also ranges south into Central and South America. Its scientific name is Aramus guaranauna, the latter part being the Tupí name for it. Until 2018, it did not occur south of Bahia Blanca, Argentina (at least not in eBird). Its core range ended closer to Buenos Aires. However, with a record in 2018 and four more in 2020 (based on eBird, which is used less in South America), it has spread up to 700 miles south, mimicking its poleward spread in North America. Northern Ohio is also about 700 miles from the Limpkin’s core range in Florida. The southernmost record, found dead at Puerto Deseado, Argentina, is at 47.8 degrees south latitude. The northernmost record, just north of Minneapolis, is at 45.2 north latitude. Like a true invasive species, one even crossed the Andes!

Limpkins are not the only waterbird associated with Southeast wetlands that are expanding north. Birders have noticed northward range expansions among the following:

- White Ibis

- Neotropic Cormorant

- Black-bellied Whistling Duck

- Purple Gallinule

- Anhinga

- Roseate Spoonbill

- and even Snail Kite, Swallow-tailed Kite, and Mississippi Kite

Many of these are actually declining in Florida (or Louisiana) as they increase in the north.

Indigenous Americans relied on observations of nature to provide information about weather, or when certain plants could be planted or harvested, or when certain fish or game were available. An Anhinga in New York, a Purple Gallinule in Ohio, White Ibises nesting in New Jersey, all of which have happened in this year – would be portents of change – or doom.

Miners kept canaries in coal mines to monitor the atmosphere. A sick or dead canary meant dangerous conditions in the mine. But imagine their surprise if their mine was suddenly invaded by a hundred canaries. That would mean something was amiss outside. Limpkins are becoming those canaries.

BREAKING: One day after posting this, a first record for Ontario, Canada.

UPDATE IN JULY 2023: Limpkin has reached Pennsylvania.