The Caspian Tern colony, the one across the bay from the Port Townsend waterfront, was just wiped out by avian flu. Nearly. At the start of the summer, we estimated the colony at about 1,800 adults. So far, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) – in five trips to the island, roughly once a week – has picked up over 1,100 dead adults and 500 dead chicks.

This is painful on several levels.

First, this colony, on Rat Island just off the tip of the spit at Fort Flagler Campground, is a relatively new phenomenon. Analysis of satellite images suggest it began last year. Unfortunately, in 2022, in two attempts, about 500 to 1,000 adults produced maybe a dozen fledglings. The first attempt was wiped out by human disturbance. A minus-four tide on the Fourth of July enticed many campers to walk from the spit to the island. I personally watched through my scope as a couple with a dog (on a leash) walked right up to the colony, putting all the birds up in the air, and stood there, naively enjoying the birds and filming them with their phones. Unbeknownst to them, gulls were pouring in underneath the cacophonous mob of terns, no doubt devouring eggs and chicks. This is how human disturbance impacts seabird colonies. A month later, the gulls tried again. This time a coyote managed to swim across from Indian Island and had a feast. Coyotes previously wiped out a colony on the tip of Dungeness Spit.

This year we were prepared to at least address the human disturbance problem. As the Conservation Chair of Admiralty Audubon, I reached out to State Parks and WDFW. They contacted the Friends of Fort Flagler, who created a team of 25 volunteers to serve as docents during extreme low tides to intercept and educate beachgoers about the terns – and the harbor seal haul-out next to it. WDFW put up signs around the island to educate kayakers.

Everyone was trained and more birds than ever came to nest. They seemed to be doing great. Most were on eggs, and we estimated they were just about to hatch. Then, on July 10, Sam Kaviar, a naturalist guide who runs Olympic Kayak Tours, noticed a dead tern. Not a big deal, I told him, unless you start seeing more. Within two hours, he saw a dozen more. He called WDFW. They were nearby in a boat so came over to check it out. They collected 35 dead terns and suspected highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), also known as H5N1. They collected carcasses to run tests, which eventually came back positive.

The second painful thing is that Caspian Terns are a long-lived slow-reproducing species. The loss of chicks is one thing, but the loss of adults is a much bigger deal. Caspian Terns, the largest tern in the world, can live 26 years. Most adults live 10 to 15 years. This means they only need to reproduce themselves once every 15 years or so to sustain their population. It also means that, if you lose an adult, it might take 15 years to replace them.

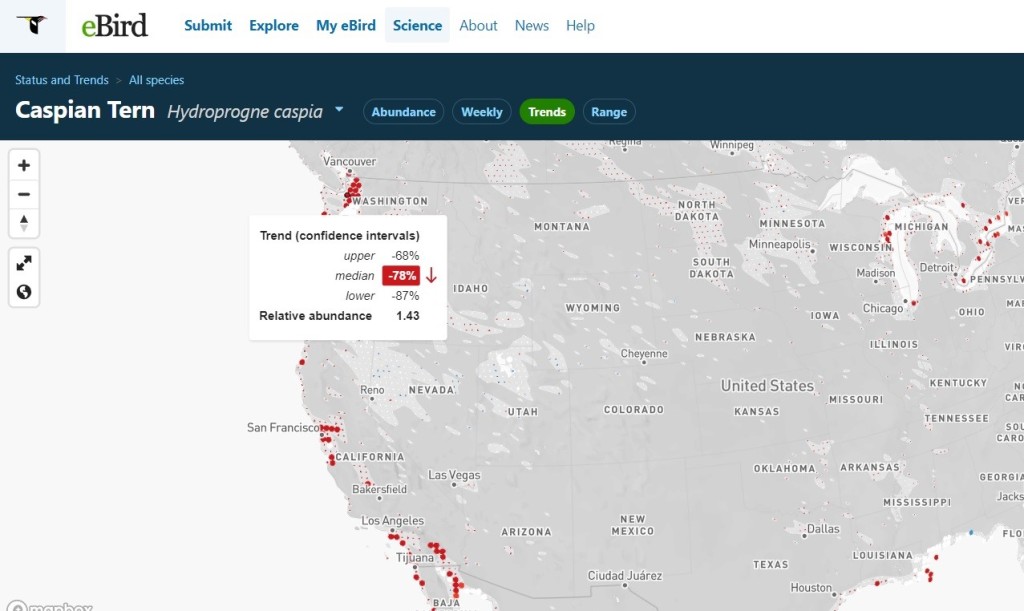

The third painful thing is that Caspian Terns are already declining, both in the Pacific Northwest, up and down the entire West Coast, and across the whole continent. The Birds of the World species account for Caspian Tern, in the section on conservation concerns, highlights their need for disturbance-free nesting sites, “Human disturbance at colonies facilitates egg predation by gulls when more wary terns are flushed from nests.”

The fourth painful thing is that Caspian Terns were deliberately pushed off from most of their other breeding sites in the Pacific Northwest in the past 15 years. They do not nest scattered across the landscape like robins or even gulls. Like many seabirds, they nest in tight colonies, packed together, one nest every few feet. In the Pacific Northwest, enormous colonies were hazed off Sand Island in the Columbia River delta by government agencies because they were eating too many salmon smolts – which are endangered because of the dams. (Note, photos of prey items at Rat Island have shown the terns eating candlefish, herring, smelt, surf perch, and juvenile salmon – the latter only toward the end of their nesting period.) Many relocated to rooftops in Seattle or to empty lots in Bellingham. In recent years, they have been hazed off there too. That is exactly why the Rat Island colony near Port Townsend grew so suddenly. It is a colony of refugees. We have photographed birds there that were banded at Sand Island, in Bellingham, even from the Tri-Cities area. This spring, as the colony was forming, local experts concluded that this was the only Caspian Tern colony in the Salish Sea.

Now 80% of them are dead.

Like Covid, HPAI has recently become part of our world. The United Nations issued a concise report about it in July 2023. They open with this: “H5N1 high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) is currently causing unparalleled mortality of wild birds and mammals worldwide…” They describe it as unprecedented based on the scale of mortality (often approaching 90%) and geographic spread (nearly worldwide). In Washington, it was first detected last winter in waterfowl (mostly Snow Geese) in the Skagit Flats.

This summer’s outbreak at the tern colony is the first known incidence of HPAI in wild birds in the breeding season in Washington. A smaller outbreak is on-going among Caspian Terns at the Columbia River delta. Fears that it would spread to the harbor seals or dogs at the Fort Flagler campground have not materialized. Some dead gulls, especially chicks, have tested positive, though in general, the gulls have been much less affected. There are several hundred “Olympic Gulls” – Glaucous-winged x Western Gull hybrids that nest at Rat Island near the terns. Bald Eagles and Black Oystercatchers are also present near the colony and potentially vulnerable, though no dead birds of these species have been found. The largest seabird colony in the region is at Protection Island, with over 10,000 Rhinoceros Auklets. That is only nine miles away as the tern flies. While terns forage near Protection Island, and auklets forage near Rat Island, there has been no evidence of transmission to the auklets. In fact, HPAI is unknown in alcids so far.

Hope remains. On my last visit to the island, on August 11, there were still approximately 350 adults. Some were flying into the colony carrying fish. On the beach, I could see about a dozen chicks of varying ages, adults offering them fish, as well as a few dead adults and others that appeared sick. I am hopeful that over 10% of the adults will survive. That sounds pathetic, but it’s a start. Perhaps they will be immune to avian flu and so will their offspring. We don’t know yet. And, despite the carnage, it looks like this colony may actually produce more fledges than last year. So that’s another start. Chicks leave the colony about 45 days after hatching. That should be soon for some of them. They can’t get away fast enough.

Thank you for this nice summary. I’m just seeing today that USFWS have detected HPAI in a report of Common Murres from Dillingham (Bristol Bay area of Alaska). I’m surprised that it was unknown in alcids before this actually. You can search for the Alaska report here:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-wild-birds

LikeLike