At 9:30am on August 17, that is, yesterday, I got a text from another birder. A Nazca Booby had just been seen from Discovery Point near Seattle. What’s more, we knew exactly where the bird was now; it was perched on the bow of a barge being pulled by the tug Seaspan Raider.

The Nazca Booby is a tropical seabird that breeds exclusively on the Galapagos Islands. When not nesting, it occurs at sea in the eastern Pacific, generally between central Mexico and northern Peru.

This was Washington’s third record. The first, quite possibly the same bird, was on August 14, 2020, in pretty much the same part of Puget Sound. The second was a few weeks ago also off Seattle. That one was an immature, not an adult, so we know it was a different individual. It then showed up off Victoria, providing Canada with its third record.

The Nazca Booby first arrived in the United States in California in 2013. I actually played a role in that first record, a dead beachcast bird found in the aftermath of an oil spill. Working for the state’s spill response, I brought it to the attention of the California Bird Records Committee and had experts examine the carcass for identification. That bird was not a one-off event; it was the beginning of an invasion. There were a few scattered records in the following years, followed by an explosion of 26 records in 2018 and 21 in 2019. After that, California removed the species from its “review list”. While some of these records may have been the same individuals, it is remarkable that a tropical bird previously unheard-of in the US was suddenly widespread. Oregon got its first two records in 2018 and 2019.

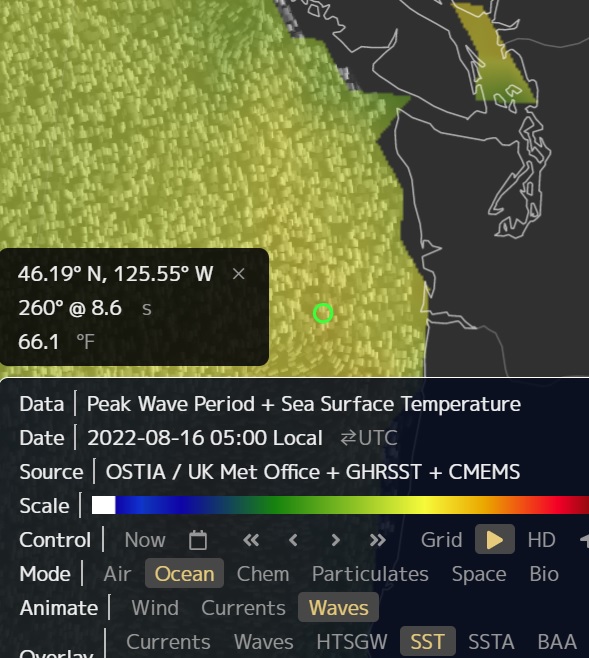

Checking sea surface temperatures, I see that the water off the Washington and Oregon coasts is reaching 66F in places, only 4F cooler than on the south side of the Galapagos. Zooming out, it is easy to see a route from there to here where the bird never had to encounter sea surface temps under 60F. The Strait of Juan de Fuca is in the low 50s, but it does approach 60F near Seattle.

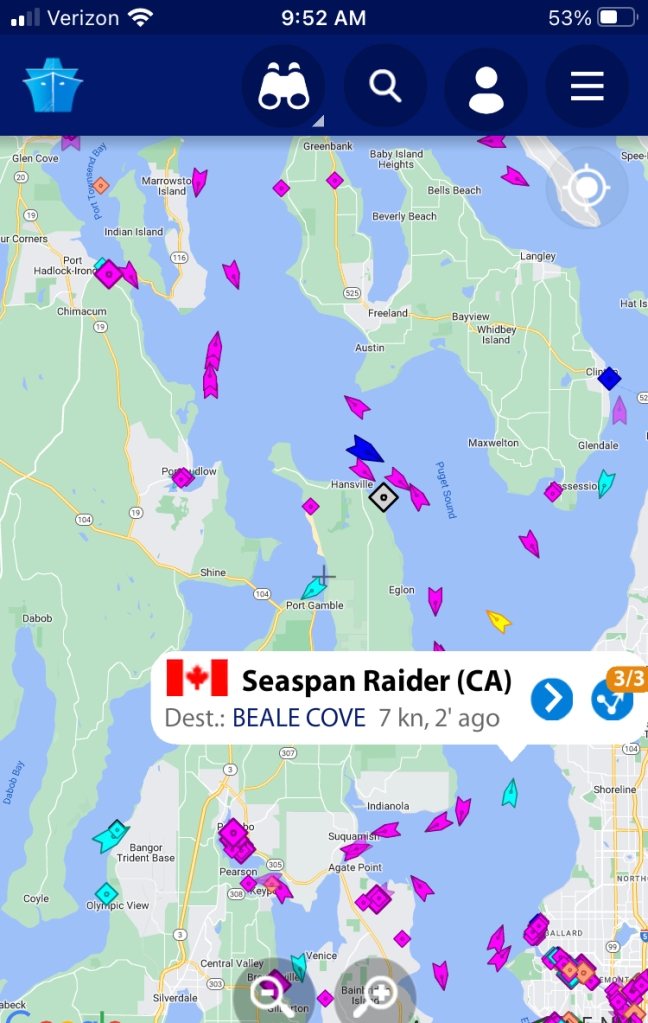

I opened the MarineTraffic app and quickly located the Seaspan Raider. It was southwest of Edmunds, northbound at 7.3 knots. I calculated it would arrive off Port Townsend between 1 and 2pm. Birders scrambled, heading to various coastal promontories on both sides of Puget Sound. I headed to Point Wilson, where Puget Sound effectively ends and meets the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The tug, bound for Canada, would have to pass by me here.

Reports came in. The bird had flown off the barge. It was in the water off Edmunds. It took off. It was seen from both sides. No one knew where it was.

This wasn’t the only booby in the Salish Sea at the moment. A Brown Booby had been photographed a few days earlier near the San Juans. That was yet another tropical seabird that had already invaded the US, with records from over forty states, including Alaska. Two decades ago, this would have been unimaginable. And this summer, 2022, was already noteworthy across the Midwest and East Coast for the mass invasion of waterbirds typically found only in Florida or the Gulf Coast. Limpkins, Wood Storks, White Ibis, Roseate Spoonbills and many others were showing up hundreds of miles north of their previously known ranges.

Scrolling thru the American Birding Association Rare Bird Alert nationwide posts, limited to just mega-rarities, here is what pops up: Brown Booby in Oklahoma, Neotropic Cormorant in North Carolina, Brown Booby in Wisconsin, two Swallow-tailed Kites in Ohio, Limpkin in Wisconsin, Neotropic Cormorant in Michigan, White Ibis in New York, Wood Stork in Pennsylvania, Heermann’s Gull in Alaska, Limpkin in Illinois, Nazca Booby in California, White Ibis in Nebraska, etc. And that doesn’t even get us back to August 1. These are all birds, mostly aquatic birds, well north of their normal ranges.

Our current rate of climate warming hasn’t been seen since the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) 55 million years ago. Then, there were alligators within the Arctic Circle. Kind of like Nazca Boobies are now a thing in Puget Sound. Actually, our current rate of warming is much faster than then. During the PETM, the climate warmed 5C in five thousand years. The current rate of warming is eighteen times faster. Then, no one would have noticed. Now, there is 1C of warming – and, with it, dramatic changes in climate and ecology – within the lifespan of a single bird. Some seabirds are showing us that they can keep up, thanks to their ability to fly long distances. I’m not sure about the alligators. Or birds that depend, say, on oak trees. The birds can fly, but the oaks can’t.

Two hours passed. I was ready to give up and head home, my only consolation being “MAMU CF”, a Marbled Murrelet making a provisioning flight across the Sound, carrying a fish to its single chick somewhere on a moss-covered Doug fir branch a hundred feet above the forest floor, probably in the Olympic Mountains. I’d only seen that once before. Much of their range in California has been lost to fires in the past five years, so this Olympic chick is important.

One birder, who was unable to search for the Nazca Booby, called some of the local orca boats, as he worked on some of them. He let them know about the bird, as some were near it. About twenty minutes later, texts came in. They had re-found it! It was back on the same barge, now approaching Marrowstone Point. I spun my scope south. There, beyond the ferry lane, I could make out the red and white structure of the Seaspan Raider, pulling its barge, all blurry and shimmering in the distant heat mirage, slowly chugging toward me.

Taking advantage of the outgoing tide, the Seaspan Raider was now hitting 9 knots. It is powered by two Niigata 6m G25HX diesel engines. I don’t know what kind of gas mileage it gets, but, because it presumably refueled in Washington, most of its fuel is likely conventional diesel, but a small component may be renewable diesel.

Renewable diesel is not the same as biodiesel. Biodiesel can be mixed with conventional diesel, but only in very small amounts, like 2%. Renewable diesel, on the other hand, is molecularly identical to conventional diesel. It’s a relatively new invention. Made from non-petroleum sources, such as plant and animal material, it is to conventional diesel what corn syrup is to sugar; it is a “drop-in ready” alternative fuel. It can be mixed with or substituted for conventional diesel seamlessly, with no change in gas pumps, pipelines, or engines. In fact, it burns slightly cleaner, so engines last longer. It emits fewer particulates and, most importantly, its greenhouse gas footprint is up to 80% less. Its use is already widespread in California, where two of the state’s largest refineries no longer take petroleum crude.

This is the kind of thing that should have been developed thirty years ago, just after James Hansen of NOAA briefed congress on climate change in 1986. Now it’s late. We’ve already had more than 1C of climate warming, with more coming and probably ten feet of sea level rise built into the system. Stopping carbon emissions is no longer a suitable goal. We’ve already pushed the cart down the ramp. It’s rolling. We need to reverse climate change, to change that ramp so the cart rolls back to where it was. That will require actually sucking CO2 out of the air – negative emissions – which will certainly take a hundred years under the most optimistic scenarios. So get ready for more boobies, maybe even Limpkins and alligators.

Aside about Washington: Washington further delayed action a few years ago when the Department of Ecology required an Environmental Impact Statement from Phillips 66 to convert their refinery at Cherry Point to make renewable diesel. That is to say, Phillips needed to jump through major permitting hurdles because they were changing – that is, reducing — their greenhouse gas emissions. Phillips didn’t want to wait the several years required for this, so they promptly moved their operation to California. Governor Inslee tried to intervene and save the project, but it was too late. Now BP is picking up the baton in Washington.

Renewable diesel is already in widespread use in trucks, especially in California. The ferries in San Francisco Bay are powered exclusively by it. Because diesel is similar to jet fuel, and made during the same refining process, refineries also produce what is called sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). Aircraft are currently permitted to fly with up to a 50/50 blend of SAF and conventional jet fuel. Boeing promises jets that can fly with 100% SAF by 2030. We’ll be approaching 1.5C of warming by then. Nazca Booby will almost certainly be off the rare bird review list, at least in California. Brown Boobies will be breeding on the Farallones and prospecting further north.

I watched as orca boats came and went from the barge, photographing the Nazca Booby. I was told it was on the starboard side of the roof of the little structure on the bow. The tug and barge continued up Admiralty Inlet until it was straight out from me, as close as it would pass. Slightly more than halfway across the channel, it remained blurred in heat mirage. I could see fuzzy white dots on the described rooftop, but I couldn’t tell you if they were Nazca Boobies or gulls or volleyballs. In birder’s lingo, this was going to be a ‘dip’, even though I knew exactly where the bird was and was looking at it.

Mathematically, this would be at least the sixth time a Nazca Booby had passed this point, my point, my sea watch. And this time I was here, ready and waiting, and still I couldn’t see it. Were it not for the texts and the orca boats, I’d never know it was there. I kept my scope glued to it, hoping it would lift off in a distinctive flight and head directly toward me, where it would join the Caspian Terns and plunge dive right in front of me as I clicked my camera in ecstasy. But it didn’t. The tug and barge chugged north.

The bird was last seen at Partridge Point on Whidbey Island, still riding the barge. It was off the barge by Rosario Inlet. I’m guessing it jumped ship and headed toward Victoria or Smith Island.

The barge’s destination was the Lafarge Texada Quarrying Ltd. limestone mine north of Vancouver. Limestone is critical to making cement. The cement-making process is responsible for 8% of the world’s carbon emissions. Part of that is from the energy used in production, which requires a kiln heated to 1,400 degrees Celsius. But most of the emissions comes from the limestone itself. Forty percent of the weight of limestone is CO2, and this is burned off in the process. There are efforts to improve the cement-making process, to make it less dependent on limestone, to reduce its carbon emissions. That’s all coming in the future.

I’m wondering about the ancient Nazca civilization in what is now Peru. It was dependent on a remarkable network of underground aqueducts that delivered mountain water to their arid home. There’s a theory that they over-harvested a certain tree, which led to erosion of riversides during heavy rains, destroying their water delivery system. I wonder if they had meetings about the problem, if they had new policies in effect, at least at the end, when it was too late.

It’s supposed to be 95F in the Seattle suburbs today. I’m not worried about missing this Nazca Booby. There will be more.