Before I get into this, here is a little bit about me. My pronouns are he/him. I am a citizen of Cherokee Nation and white-presenting (that is, I look like a white male).

1. Everyone likes birds.

Everyone. Regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, race, socio-economic status, political orientation, urban or rural background, if you asked them if they like birds, they’ll say yes. They may complain about a few problem birds that crap on their car, but in general, people will say they like birds. And they put their money into it. The public spends about as much on backyard bird feeding as it does on movies and television. Birds are beautiful. They fly. They evoke freedom and encourage us to dream.

2. Birding is a pathway to greater environmental knowledge and belief in science.

To get to know birds is to learn about migration, seasons, weather, ecology, habitats and threats to habitats. To watch birds is to see the human/nature interface in bright daylight – the dog that chases the endangered Snowy Plover, the development that removes the woods on the edge of town, the cat that kills the sparrows that migrated here from central Alaska. Birders overcome Nature Deficit Disorder. They become ecologically educated, understanding environmental issues.

3. Birders support environmental causes and the fight against climate change.

In general, birders are environmentalists. Cooper et al (2015) found that birders (and hunters) were “4 to 5 times more likely to engage in conservation behaviors,” such as supporting environmental causes. They concluded, “Strategies that include programs to encourage both hunting and birdwatching are likely to bring about long-term gains for conservation.”

4. There are far fewer birders than there should be.

There could be a lot more, but certain demographics are underrepresented in the birding community. This includes non-white ethno-racial groups, younger people, and less educated people.

Ethno-racial categories

In their 2021 paper, Racial, ethnic, and social patterns in the recreation specialization of birdwatchers: An analysis of United States eBird registrants, Jonathan Rutter et al (no relation to Jordan Rutter of Bird Names for Birds) analyzed a survey of 30,000 eBird users. That paper, especially Table 3, is the basis for the graphs presented here. Note that the eBird data comes from 2016-17 and the US population data comes from 2011-15. There has almost certainly been an increase in diversity in both datasets since then, especially the eBird data. In 2016, eBird was still fairly limited to certain social circles. The number of eBird users has nearly doubled since then. A new survey would show far more diversity.

Going back further, in 2005, John Robinson found that, while the majority of Blacks expressed a high level of interest in the environment, very few participated in birding (or other outdoor activities) and very few had ties to environmental organizations. He famously said that “the average bird watcher will meet no more than two or three African-American bird watchers over a 20-year period.” That has changed.

This underrepresentation has been correlated with other outdoor activities, as well as membership in conservation organizations – and especially in leadership – more on that below.

With respect to birders, are we talking about backyard feeder watchers or avid listers? Rutter et al dived into this, what is termed the degree of “specialization” – how avid and dedicated one is. They asked questions such as: How often to you travel from home to look for birds? How often do you use eBird? Do you own a scope? How many species can you identify by ear? They found no effect on specialization by race. In fact, race, age, gender, knowing a close friend or relative who is a birder, income, and education combined only “explained 6.7% of the variability in how central birdwatching was to respondents’ lives.” No matter what your background, once you start, you are equally likely to head down various paths of birding obsessiveness.

The huge racial divide then, occurs at step one, the decision to start looking at birds. After that, the birds do the rest. Rutter et al concluded, “Future efforts to diversify the birdwatching community, therefore, may be most effective if focused on increasing initial participation rates of underrepresented groups.”

Gender

Nearly every study shows there are slightly more female than male birders. This holds across all ethno-racial categories. (Note, this data, collected in 2016-17, makes no reference to non-binary or refuse-to-state responses. The total in the graph sums to 99.9%. I don’t know if this is rounding error or reflects alternative responses, or if alternative responses were removed from the analysis.)

Regarding degree of specialization – how avid and dedicated and experienced they were – men scored higher than women on these questions, but only by a small margin, just 1.7 points on a scale with a median score of 17 (e.g. perhaps men averaged 17.7 and women 16.0).

While there are lots of women birders, and they are nearly as specialized as men, they are far less likely to be in leadership. Most prominent birders – the ones who lead Christmas Bird Counts, serve as eBird reviewers, serve on state or national bird records committees, work as bird guides, speak at conferences, write field guides, etc. – are white men. (A notable historical exception: the first field guide that popularized birding for the public was written by Florence Merriam Bailey in 1889.)

Looking at the top 10 or 20 birders on eBird – in any state or region for any given year – women are typically only represented by a few individuals, whether looking at number of checklists submitted or – a decidedly more competitive and obsessive measure – number of species seen in a given year.

The dearth of women in leadership continues across environmental organizations in general. In 2015, Dorceta Taylor looked at 324 such groups, finding that “though females exceed males on the staff of environmental organizations, women are underrepresented in the top leadership echelons of the institutions.”

In academia, however, change is afoot. While ornithology professors are still mostly men, this varies across universities. The new generation is far more diverse. At the 2023 AOS annual convention, women won 19 of the 23 awards. Additionally, diversity, equity, and inclusion topics were prominent among the papers and presentations.

Age

For all ethno-racial categories, birders (in green) average older than the overall population (in blue), with the breakpoint generally in the upper 40s. Again, this data is dated, and more young birders now avidly embrace eBird. White birders skew older more than any others, and have, in proportion to their population, the fewest young birders and the most older birders. Asians are at the other end of the spectrum, with the most young birders as a proportion of their population. Asian young people are more than twice as likely to take up birding than their white counterparts. Latinx, Blacks, and Native Americans are between, in that order, with the Latinx closer to the Asian graph below.

The take home here is that there are many potential birders among those under 45 – and even more under 35 and yet more under 25. And young people of color are more likely to take up birding than white young people.

Education

Relative to the overall population, birders are extremely educated. One big caveat here: It could be that there are plenty of less-educated birders, but they just don’t use eBird as much. The survey showed that nearly half (48%) of the 30,000 eBird users surveyed had advanced degrees, compared to just 12% of the other whites (age 18+). This is even more true among birders of color. Latinx birders were 10x more likely than other Latinx to have advanced degrees. Blacks and Native Americans were 6x more likely. A person with an advanced degree is 13x more likely to be a birder than a person without a Bachelors.

The October 2021 issue of Birding magazine explored the least birded counties in the nation, based on the number of eBird checklists. Of the bottom 20, 18 were in Kentucky, Mississippi, or West Virginia, all small rural counties. Sure, they have fewer people than a major metropolitan county. King County (Seattle) generates many times more eBird checklists in a single day (about 700/day) than these counties have in the history of eBird (all with fewer than 100 checklists total). At the same time, I wonder if these low rural county birding rates are partly explained by the education graph above.

Hunting is popular in these areas. 60% of duck hunters are from small towns or rural areas. Surveys of duck hunters show some similarity to birders (e.g. predominantly white), but a different trend regarding education. While they still skew slightly toward more educated, their graph mimics the general population fairly closely.

As someone who learned to bird from my father’s duck hunting blind in a small rural county, I can also assure you that plenty of lesser educated hunters and anglers love the outdoors and know birds pretty well. An advanced degree is not required for bird identification, and certainly not to be an avid birder. Lesser educated rural people could become birders. The take home here is that there are millions of potential birders among those who are less educated, and certainly among hunters who support environmental causes.

Income

Despite their exceptionally higher education level, birders do not earn more money than the general public. This is pretty consistent across all ethno-racial categories. If anything, birders earn slightly less. For example, 24% of the general public earns between $100K and $200K per year. Only 21% of birders do.

To summarize where we are, there are three main demographic groups (which no doubt have some overlap with each other) that bird at lower rates: people of color, younger people (especially whites), and less educated people. While there have no doubt been significant increases in these groups since this survey was done, it is still clear that there is a lack of birders of color and women in leadership roles. This is where there are opportunities to grow birding and the environmental movement in general. And research suggests that knowing other birders is key to start birding.

5. Because underrepresented people are not included – and are actively excluded.

In recent years, there has been a rise in historically-marginalized identity-based birding clubs and ornithological organizations, a kind of alternative birding universe where people can experience birding in a closer-knit community with different social rules, expectations, and styles of communication than in larger white-male-dominated birding circles. Here are some of those groups (and a podcast):

- In Color Birding Club – we strive to make the birding experience a positive one for BIPOC folks and their allies.

- Anti-Racist Avid Birders – dedicated to making the outdoors—and birding in particular— accessible and safe for people who find themselves under-represented or unacknowledged in traditional birding communities.

- Always Be Birdin’ podcast – aims to change the narrative of birding. How we bird, where we bird and who is birding. Join me as I go out into the field with BIPOC birding experts, novice baby birders like myself and nature enthusiasts.

- Freedom Birders – a racial justice education project.

- Melanin Base Camp – to increase ethnic minority and LGBTQ+ participation in the outdoors (more focused on adventure sports).

- Feminist Bird Club – dedicated to promoting inclusivity in birding.

- The Galbatross Project and Female Bird Day – focusing attention on the importance of female birds.

- World Girl Birders – to find solutions and creative approaches to supporting women in birding.

- Rainbow Lorikeets – the AOS caucus of the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals.

- QBNA (LGBTQ+ Birders of North America) – to facilitate communication among LGBTQ+ birders and their allies

- Frontiers in Ornithology – to educate and inspire youth to take their passion for birds to a higher level.

(Please let me know of more groups I should add to this list.)

There are also many local groups like the ones above, as well as for young birders. And there is Black Birders Week, supported by a wide range of organizations.

Here are some important essays and books on the same themes:

- J. Drew Lanham. 2016. Birding While Black.

- Joan E. Strassmann. 2021. Slow Birding: The Art and Science of Enjoying the Birds in Your Own Backyard.

- Christian Cooper. 2023. Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World.

- Thomas C. Gannon. 2023. Birding While Indian: A Mixed-Blood Memoir.

- Sydney Anderson and Molly Adams. 2023. The Feminist Bird Club’s Birding for a Better World: A Guide to Finding Joy and Community in Nature.

Dominant birding culture

Birding is a pseudo-academic hobby that can take on the vibe of a competitive academic department with a strict, though unwritten, code of behavior. As with any hobby, there is a whole lingo associated with certain activities, especially chasing and listing. Some of it sends subtle messages about how to be a birder, and what it takes to be an Alpha dog.

I drank the Kool-Aid for years. I thought these things were important to cultivate the right kind of birders. I was a gate-keeper. Now I realize enforcing a specific culture and birding etiquette can be a turnoff to new birders, especially those from different demographic backgrounds not comfortable navigating in white male spaces, much less a very specialized and potentially competitive environment. We are, after all, talking about enjoying nature here.

Let’s take one example. Among the cardinal sins for those seeking birding Alpha status is this: do not make an identification mistake in public. When I was a young birder, I loved public debates and discussions about golden-plovers and dowitchers, vireos and accipiters; that’s how I learned. They seem harder to find now – not the birds, the open discussions.

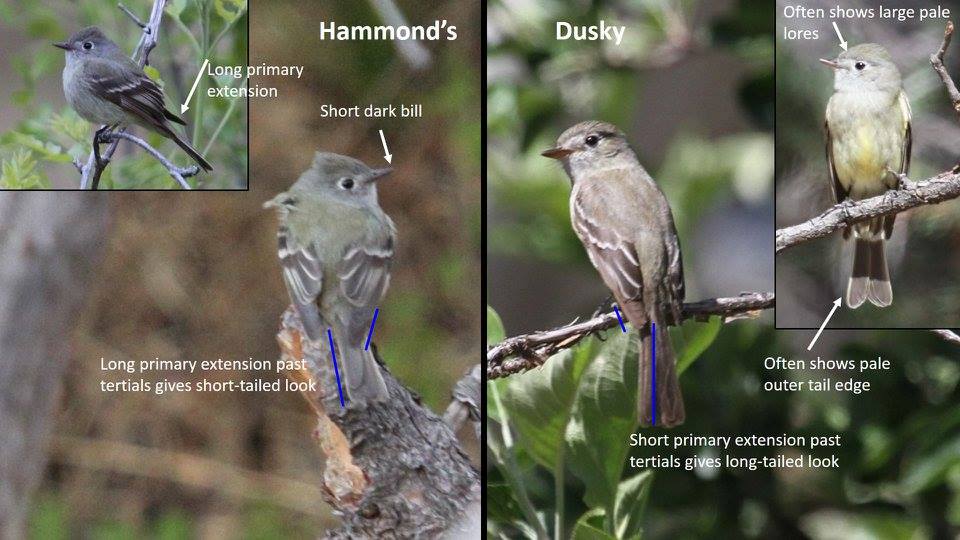

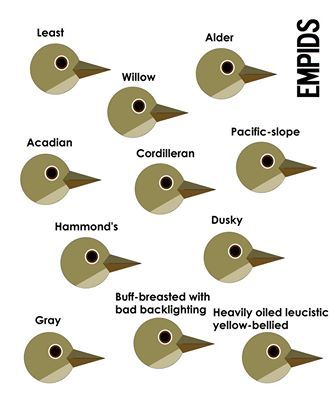

I was recently called “incredibly brave” by a teenage birder for publicly calling attention to a difficult id problem between a rare vagrant and a common species, positing that the bird may be the vagrant. The teen had already figured out the code. The bird, as the odds have it, turned out to be the common one. Later, people were thanking me for initiating the educational discussion online. I’m not brave, just jaded enough that I’m trying to care less about my reputation and am trying to model ‘learning in public,’ which is critical to learning about birds. If gulls and Empidonax flycatchers teach us anything, it’s that everyone must be allowed to make mistakes.

The concept of “slow birding” recently evolved as an even more radical counter to the competitive and obsessive aspects of birding. Slow birding is about bird/life balance, where birding can be an act of mindfulness. The key point is this: There is no one right way to enjoy birds.

Institutional structures

Across academia and many workplaces, we have seen increased diversity over the past four decades. The US Congress has gone from 3% women in 1980 to 28% today. The same probably could not be said for bird record committees, birding tour guides or birding conference speakers.

One way the birding community creates obstacles to diversity is thru various institutional structures and processes. Sometimes it’s just the name. Outside the affinity-based birding clubs described above, most local clubs are “Audubon societies.” In addition to stereotypes of older white people peering thru trees at warblers, both the words “Audubon” and “society” are turnoffs to youth and people of color. It’s a shame because many local groups do great outreach and local conservation. They can be key points of entry for new birders.

I know many who used to work for National Audubon who now boycott them on principle. Some organizational clarification: National Audubon and various state affiliates (e.g. Audubon California, etc.) are all part of a single 501c3. That is the entity that has refused to change its name. Local Audubon societies, however, are separate 501c3’s; they can change their name any time they want. Seattle, Golden Gate, and many others have done so. The challenge now – and what has caused so much delay – is how to do so in a coordinated way, now that National is failing to provide a model for change.

Sometimes the barriers to entry are more substantial than the name; sometimes it’s the actual bylaws. The most dramatic example involves the North American Checklist Committee (NACC) of the American Ornithologists Society. They oversee lumps and splits (and, until recently, English bird names as well as scientific names). The members have advanced degrees in ornithology and are expert taxonomists. That’s no surprise. What is astonishing is that the members of this committee serve unlimited terms and new members are chosen by pre-existing members. Thus, turnover is slower than the US Supreme Court. Some of the members have been on the committee for over 30 years. Five of the eight members who were on the NACC in the year 2000 are still on today. (It has 11 members today, plus two Latina members from Mexico and Central America.) Only one of the nine Supreme Court justices today was there in 2000. The aim, of course, is doctrinal stability, but it comes at a cost. Such policies limit opportunities for younger academics to even aspire to the committee, and certainly retard diversity on the committee.

In the birding world, many state record committees, which oversee state records and evaluate observations of rarities (declaring what is “countable” for listers), have only slightly less-restrictive policies, often resulting in a revolving door of white males. For many of these committees, vacancies are filled only through the nomination by and approval of the existing committee members, just like the NACC. Given that these committees have only a dozen members at most, and there are hundreds of expert birders in most regions, it seems hard to believe there are not women and people of color qualified to serve. Some committee members I’ve spoken to say they try to reach out to other demographics to nominate them, but their efforts have not succeeded.

I’m not questioning the qualifications or bird decisions of these committees. Their service is commendable. Regardless, the appearance is of an entrenched aristocracy that appears to exclude women and people of color.

Even Christmas Bird Counts (CBCs), usually terrific opportunities for outreach, are not immune to institutional barriers to entry. There are some CBCs that are run as private clubs, closed to outsiders and beginners. On others, beginners are shunted off to less exciting routes.

Public gate-keeping

While there are plenty of legitimate questions and alternative perspectives for any issue in birding, recent discussions about birding and diversity issues (e.g. regarding committee membership and the re-naming of certain birds) have often crossed a line, being particularly insensitive to women, younger birders, and birders of color.

Recently, a friend of mine, a younger person of color and a beginning birder, joined a local former-Audubon bird club field trip for the first time. As the group began to gather – all older white men and women – the leader initiated a group gripe session about the proposed bird name changes.

I don’t know exactly what words were said, what arguments were made. Just the big picture – that an initiative, motivated by diversity and inclusion concerns, is being most criticized by white men over 65, the exact demographic that is most included and overrepresented in leadership positions – is not a good look.

(I acknowledge there are many prominent white male birders who are supportive of the bird names proposal: Kenn Kaufmann, David Sibley, Nate Swick.)

Apparently it is too much to hope that birding’s enormous diversity problem would somehow frame the overall conversation. Instead, some of the common arguments are premised as if the only people in the room are white, using entire frames of reference that exclude marginalized people from the conversation. In a public forum, these arguments essentially declare birding as white space.

Three examples that my friend may have heard:

1) When society’s morals change, the present morals should not be applied to people of the past.

~ This is a white issue. By “society,” they mean white society. Blacks have always opposed slavery, Natives have always opposed ethnic cleansing. We can debate how much white society has changed. What has most obviously changed is that now there are other voices at the table. These voices have grown up with different narratives about history and about how their families were impacted.

2) This is “wokeness” and “virtue-signaling.”

~ These are accusations by whites of whites. One doesn’t say a Black person is virtue signaling when they talk about police brutality. And one doesn’t call a Native woke when they talk about tribal sovereignty. No, woke and virtue-signaling are modern variations on “n-lover” and “squ*w men.” The use of these terms presupposes that the new initiatives are coming from white liberals. In fact, there are lots of people of color involved.

3) Competency and quality (for example, as a committee member) should always come before diversity.

~ This is insulting to women and people of color. It echos claims that underqualified people are given positions as charity, as “diversity hires.” Women and people of color have their own narrative – that they work twice as hard to get half as far. That they are, in short, often over-qualified. Diversity strengthens organizations so they don’t make the kinds of mistakes we are witnessing today, and also serve as inspirations to attract new people from across the demographic spectrum.

Another version of this is to point out how accomplished and important the angry white men are – that the bear has been poked too much, and thus the pace of change should slow down. Such arguments are both circular and ironic. The whole point is that there should not even be a bear. And if the bear is so angry about a symbolic measure, what about more concrete measures? We should all be on the same team, building a better world for birds and birders.

My friend didn’t go into detail about what arguments he heard at that bird walk. All he told me was that he won’t be going back.

6. Making birding more inclusive requires structural change and specific actions.

If the online debates don’t offer concrete solutions to make birding more inclusive, all those affinity-based groups I listed above do. Those birders are already acting! Some of the books I highlighted above are filled with ideas. I’m going to do a separate blog post later on creative ideas to increase diversity in birding. In the meantime, here are a few:

- Increase diversity in leadership positions. Both Robinson (2005) and Rutter et al (2021) found that a lack of role models is a significant barrier to entry. Robinson compares Black participation in birding to golf, noting that, after the rise of Tiger Woods, the number of Black golfers nearly doubled in four years.

- Change the bylaws of committees to allow for greater turnover (thru meaningful term limits). Use external nominations and external appointments or voting to fill vacancies.

- National Audubon, which oversees CBCs, should require all CBCs to welcome beginners, and create and provide tools to make that easier. (There are some awesome examples from Canada. Check out this one, where a youth team was given the prized pelagic route on a cool Zodiac donated for the day by a local orca-watching company.)

- Local clubs should offer a range of birding opportunities, targeting different demographics (e.g. youth, women, underrepresented ethno-racial groups). In Robinson’s survey, one respondent said that “a change in advertising and possible programs scheduled in the right areas, along with support from Blacks who back this effort, can change everything.”

- Along with trips to Ecuador, promote 1MR and 5MR birding (birding within a 1 or 5 mile radius of your home), which increases bird/life balance, knowledge of local birding patches and environmental issues, local community, and birdability for those unable to travel long distances. It’s also a great way to find rare vagrants, especially at feeders in winter. In a similar vein, promote county birding and environmental big days and big years (walking and/or biking).

- Outreach to hunters, who have a lot of commonalities with birders. We can be allies.

Finally, if you comment on this blogpost, don’t just say why something won’t work; focus on solutions. Positive suggestions for edits are also welcome. We’re all on the same team, birds are for everyone, and they need more allies.

References

Cooper, C., Larson, L., Dayer, A., Stedman, R. and Decker, D., 2015. Are wildlife recreationists conservationists? Linking hunting, birdwatching, and pro‐environmental behavior. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 79(3), pp.446-457.

Robinson, J.C., 2005. Relative prevalence of African Americans among bird watchers. In In: Ralph, C. John; Rich, Terrell D., editors 2005. Bird Conservation Implementation and Integration in the Americas: Proceedings of the Third International Partners in Flight Conference. 2002 March 20-24; Asilomar, California, Volume 2 Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-191. Albany, CA: US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: p. 1286-1296 (Vol. 191).

Rutter, J.D., Dayer, A.A., Harshaw, H.W., Cole, N.W., Duberstein, J.N., Fulton, D.C., Raedeke, A.H. and Schuster, R.M., 2021. Racial, ethnic, and social patterns in the recreation specialization of birdwatchers: an analysis of United States eBird registrants. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 35, p.100400.

Taylor, D.E., 2015. Gender and racial diversity in environmental organizations: Uneven accomplishments and cause for concern. Environmental Justice, 8(5), pp.165-180.

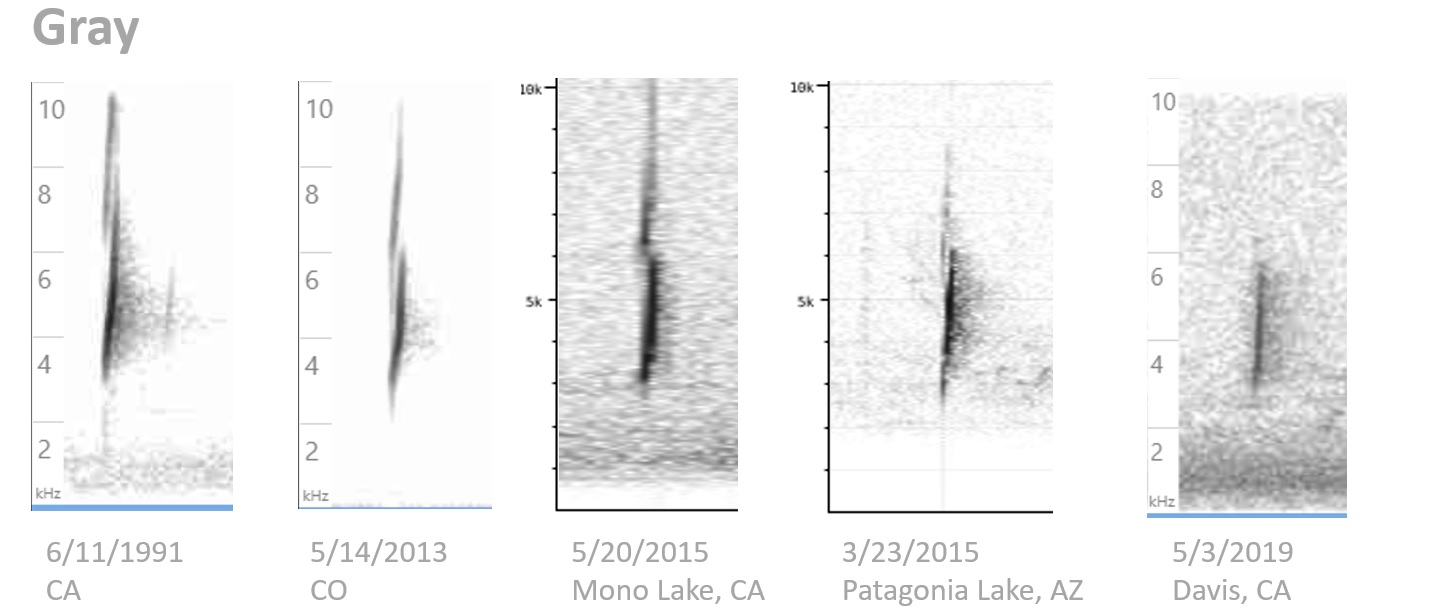

Much has been written about Empid identification. Here’s a link to the

Much has been written about Empid identification. Here’s a link to the