Here is a closer look at the eponymous (mostly honorific) names for the most familiar species in North America.

At the American Ornithological Society (AOS) Congress on English Bird Names on April 16, 2021, a host of prominent organizations and individuals endorsed “bird names for birds”, a widespread effort to rename eponymous or honorific species names with more descriptive names, focusing on their physical or ecological attributes.

This Analysis: 80 familiar species

Looking at Version 8.0.8 (March 12, 2021) of the ABA Checklist, 116 of the 1,123 species, or a little over 10%, are named after people. Of the 116 in the ABA area, two (Bishop’s Oo and Bachman’s Warbler) are considered extinct, one is an introduced species in Hawaii (Erckel’s Francolin), and 32 others are Codes 3, 4 or 5, meaning they occur rarely in the ABA area. The remaining 80 are all Code 1 or 2 and can be expected to be seen in the ABA area regularly. The following analyses focuses on these 80 familiar species.

The Birds

The first thing to note is that these 80 species come from a wide array of families and species groupings. As with all birds, Passerines are dominant, making up 49% of the list. Digging deeper, seabirds and Passerines with limited ranges (mostly warblers and sparrows) are over-represented—because they were described relatively late in the European discovery process, when honorific naming became more in vogue.

Naming Patterns

The AOU (American Ornithological Union, the precursor to the AOS) began proposing English names in its first checklist in 1886, but didn’t complete the effort – and the names were not universally accepted – until the 5th edition in 1957. Meanwhile, the scientific names have always followed a clear rule: the scientific name is set by the first published description of a species. The “bird names for birds” movement is focused on English names only.

Eponymous naming was rare in the 18th century, limited to just four of the 80 species, all emanating from Russian/German and British field work, primarily focused on the far north. The four early birds are Steller’s Eider (1769), Blackburnian Warbler (1776), Steller’s Jay (1788), and Barrow’s Goldeneye (1789).

Then, in 1811, Alexander Wilson named a woodpecker and a nutcracker after Lewis and Clark, and honorific naming was off and running, peaking in the mid-1800s.

Eponyms for the 80 Code 1 and Code 2 species are overwhelmingly honorific. Only six are named after the describer himself (Wilson’s Warbler, Sabine’s Gull, Brandt’s Cormorant, Townsend’s Warbler, Gambel’s Quail, and Cory’s Shearwater), and it’s not clear that even all of them intended for the species to have an eponym; the scientific names for the warbler, cormorant, and shearwater suggest otherwise. Wilson himself called his warbler the Green Black-capped Flycatcher and the western subspecies went by Pileolated Warbler (coined by Pallas) as late as the 1950s.

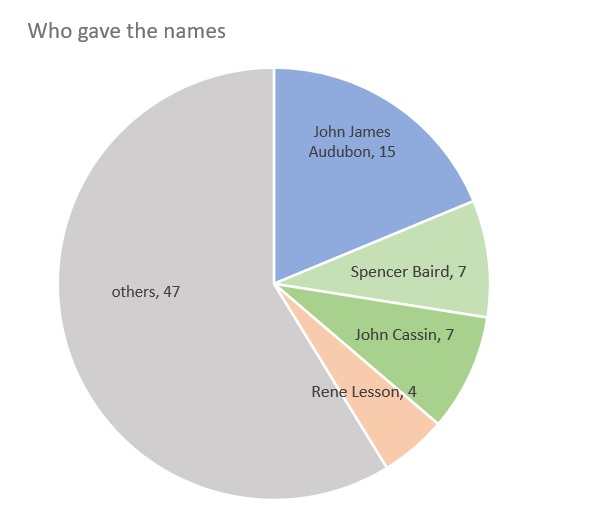

The namers were widespread – 36 different people provided the 80 names, though four stand out. John James Audubon provided fifteen of the eponymous names, Spencer Baird and John Cassin each provided seven, and Rene Lesson four. Together, these four ornithologists were responsible for 41% (33/80) of the honorific names in this analysis. In addition, many eponymous subspecies were coined by Baird.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The majority of the namers were connected to each other, with many naming birds after colleagues, who in turn named species after other colleagues. Lesson described Audubon’s Shearwater and Oriole; Audubon described Baird’s Sparrow; Baird described Woodhouse’s Scrub-Jay; Woodhouse described Cassin’s Sparrow; Cassin described Lawrence’s Goldfinch; Lawrence described LeConte’s Thrasher.

There are no examples of a quid pro quo, where two people named birds after each other, unless you count Audubon’s Warbler, described by Townsend in 1837; Audubon returned the favor with Townsend’s Solitaire the following year. Or Coues, who christened a sandpiper after Baird in 1861; four years later, Baird named a warbler after Coues’ sister, Grace.

Despite Audubon’s dominant role in honorific naming, no Americans honored him (excepting Townsend with Audubon’s Warbler); only Lesson, a Frenchman, did.

A third of the species (27 of 80) have scientific names that do not match the honorific English name. In most instances this is because the bird was accidentally described twice. Most often, they were not originally intended to have an honorific name. A person described the species and gave a descriptive scientific name, then later another person described the same species and gave an honorific name. For example, Lichtenstein described A. aestivalis in 1823, then Audubon described it again in 1839, naming it Bachman’s Sparrow. When it was realized the two were the same species, the scientific name provided by the first publication held, but, at least in these instances, the honorific English name was also given—a kind of consolation prize to the second describer. Thus, what was called Pinewoods or Oakwoods Sparrow became Bachman’s Sparrow. It’s apparent that oversight and review of “naming and claiming” was limited.

Among the 80 species in this analysis, this double-describing happened at least 18 times. Curiously, six of these were by Audubon and account for 40% of his honorific bestowments. These are Harris’s Hawk, Bachman’s Sparrow, MacGillivray’s Warbler, Harris’s Sparrow, Brewer’s Blackbird, and Smith’s Longspur. MacGillivray’s Warbler was intended to be Tolmie’s Warbler as described by Townsend; the other five have descriptive scientific names. There is one other double-described species that has a scientific honorific—Scott’s Oriole, Icterus parisorum, originally named after the Paris brothers. Most of the others have descriptive scientific names.

Cassin’s Auklet (P. aleutica) and Cassin’s Kingbird (T. vociferans) were first described, respectively, before Cassin was born and when Cassin was just thirteen. Clearly the original describers did not intend to honor Cassin. However, by the 1886 AOU checklist both carried the Cassin moniker, though there is no record that I could find how or why that came to be (and even a co-author of the auklet’s Birds of North American species account didn’t know the answer).

Interestingly, two species have scientific names derived from indigenous words: pipixcan of Franklin’s Gull is Nahuatl for the gull or possibly the Aztec region in Mexico; sasin of Allen’s Hummingbird is Noo-chah-nulth (Nootka) for hummingbird, a reference to when the species was lumped with Rufous Hummingbird. The gull was described twice, which is how it ended up honoring Franklin. The hummingbird was split, providing an opportunity for another name. Ironically, Allen’s, not Rufous, Hummingbird always bore the Noo-chah-nulth name which emanates from Vancouver Island.

Correlated with the timing, a clear regional pattern emerges. Because the common eastern species had already been described a century earlier, western species with honorific names outnumber eastern ones nearly ten to one. A map plotting the year of description with the core of the species’ range mimics European expansion – and ethnic cleansing of Native Americans – across the continent in the nineteenth century.

ADDITIONAL NOTE ADDED June 2023: I decided to compare the odds of encountering a bird with an eponym in Arizona with Massachusetts. Using eBird frequency data at the state level, I tallied 32 species in Arizona which appeared on at least 3% of all checklists in any week during the year. The most common were Anna’s Hummingbird (hitting a maximum of 33% at one point during the year), Gambel’s Quail (30%), Abert’s Towhee (27%), Lucy’s Warbler (27%), Say’s Phoebe (25%), and Wilson’s Warbler (21%). In Massachusetts, there were only 7, two of which were pelagic species (Wilson’s Storm-Petrel and Cory’s Shearwater). The most common you would encounter on land were Cooper’s Hawk (10%), Wilson’s Warbler (10%), Swainson’s Thrush (8%), Bonaparte’s Gull (5%), and Forster’s Tern (3%). As you can tell, any checklist in Arizona is far more likely to contain birds with honorific names than in Massachusetts, probably five to ten times more, depending on the time of year. This likely holds generally in comparing the West to the East.

The Honorees

As for the honorees, most were naturalists, either doing field work or promoting it (70 of 80), most were Americans (55 of 80) or at least had spent some time in North America (add ten more). French collectors dominated the hummingbirds.

Only six species honor women—or girls. Blackburne is the early outlier, a British naturalist honored by one of the German ornithologists in the late 1700s. Neither spent time in North America; the type specimen comes from South America. Curiously, the eponymic title is not in the possessive form (e.g. Blackburne’s Warbler). For reasons unknown to me, the scientific name was changed from blackburniae to fusca before 1910.

During the surge of honorifics in the mid-1800s, the only females honored were friends or family, and they only got first names. Anna, age 27 when the hummingbird was named in her honor, was the wife of an ornithologist and a lady-in-waiting in the court of Emperor Napoleon III’s wife. She was described by Audubon as a “beautiful young woman, not more than twenty, extremely graceful and polite.” Virginia was the wife of William Anderson, the original collector; she was honored by Baird at Anderson’s request. Grace, also honored by Baird, was Elliot Coues’s sister. Lucy, age 13, honored by James G. Cooper, was Baird’s daughter.

We don’t return to female scientists – and last names – until the 1900s, with Scripps, who was honored in 1939, and her bird didn’t reach species status until 2012.

Most of the honorees have no obvious indications of a checkered past (66 of 80), though most of these were quite comfortable associating with, or honoring with bird names, those who were slaveholders, white supremacists, or actively involved in killing or removing Native Americans, even while these actions were hotly debated and contested at the time among whites—and universally opposed by Blacks and Native Americans. As early as 1920, the entire concept of eponymous bird names was challenged.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The dominance of western species among honorific names with morally objectionable pasts is no accident. In wars of conquest against Mexico and Indigenous peoples, the US army sought solider-scientists who could help map new lands. In the process, they renamed land and wildlife as if it was discovered for the first time. Many of the ornithologists working in the West were attached to US military expeditions or other surveys of colonization, such as railroad surveys or the border survey after the Mexican-American War. They often served as doctors while doing naturalist work on the side. Many were likely looking for a vehicle to get into the field.

Others were active combatants, with the naturalist work coming on the side. William Clark, after the famous 1803 expedition, played a leadership role in the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans for three decades. Abert served as a soldier under John Fremont’s Third Expedition and likely participated in the Sacramento River massacre of Wintu families, deemed horrific by their contemporaries. General Winfield Scott, not a naturalist in any way, was honored by Couch with an oriole precisely for his role as the Commanding General of the US Army, which included overseeing the arrest, detainment, and expulsion of the Cherokee during the Trail of Tears. Scott had been a major party candidate for president of the United States just two years before Couch honored him with the oriole. Imagine McCain’s Oriole or Romney’s Finch.

This passage, from a 1960 article about soldier-scientists Richard and Edward Kern (who collected birds but only got a river, a beetle, and a county named after them), exemplifies the era. “Their first task… was to map uncharted Navajo country on a punitive march with the army.* It was a rich opportunity to observe Indians in their native haunts. How many men did they know at the academy in Philadelphia who would give an arm to be thus contacting Pueblos and Navajos! Moreover, the Kerns would measure a few more skulls for Morton; snare some strange lizards for Leidy; and capture for their own delight any number of bright birds from a terra incognita.”

[* This was Col. John M. Washington’s 1849 incursion in which elderly Navajo Chief Narbona was killed minutes after a peace agreement, leading to war between the Navajo and US, who had just annexed much of the Southwest from Mexico]

But why did they turn to honorific naming when their predecessors did not? Was it the spirit of conquest, of erasing the former occupants of the land, that gave them the presumption and bravado to name even the birds after each other? After all, mountains, rivers, valleys, and large regions of land were all being re-named and claimed as European. In the Southwest, many places that already had Spanish names were given English names.

White supremacy permeated the sciences. Crania Americana was published between 1839 and 1849 by Samuel Morton, a colleague of several of the naturalists. In addition to the Kern brothers mentioned above, Townsend collected skulls for him. During the same era, to support the Indian Removal Act and other similar policies, the Mound Builder Myth, asserting that Native Americans were not actually native, but that North America was originally populated by Europeans, was widely taught in grade schools across the land. The land was originally European, so the story went. This theory was eventually laid to rest thanks to the efforts of John Wesley Powell, but only after most Natives were detained in concentration camps.

In short, the scientific fields were permeated with white supremacy and a sense of white ownership. Ornithological research found itself interlocked with US military endeavors and, on the Western frontier, far from Eastern progressive voices advocating abolition and respect for slaves and Natives. In this climate, honorific naming eventually ran amok, often foundering on the rocky shores of slavery and ethnic cleansing, aka manifest destiny.

Caveat: Researching the origins of species’ names is challenging, especially for those described more than once or subject to taxonomic revisions. Corrections from knowledgeable readers are much appreciated. Regardless of errors, the larger picture, the trends regarding time and place, still hold.

Note: Updated June 2, 2021 to include Blackburnian Warbler.

I recently dug deeper and looked at what these species are called in other languages. It turns out that all of these species have alternative “bird names” in other languages.

I’ve added some thoughts addressing the question: Should we hold people in the past accountable to present-day mores?

As a citizen of Cherokee Nation, here is my personal connection to Scott’s Oriole.