There are 21 subspecies of Spotted Towhees, but only three of them occur in the Pacific Northwest. Even then, there is confusion.

Our local oregonus birds, like so many PNW subspecies, are dark and dusky. I call them Nearly-spotless Towhees. But sometimes in winter we see more spotted ones. In my quest to uncover the differences between curtatus and arcticus, the most likely candidates, I discovered there are more questions than answers.

The confusion goes back to the 1800s. To quote from Rick Wright’s Sparrows of North America (2019), the taxonomy of Spotted Towhees is a source of “much confusion.” He’s actually quoting William Brewster from 1882. Yet, 137 years later, Wright spent the next 15 paragraphs describing decades of confusion – which persists to this day.

According to the Birds of the World (BOW) species account: “There exists no review of subspecies and no modern, quantitative study of geographic variation” outside of Mexico and the Pacific Coast (which was studied by Swarth in 1913).

Because there are so many subspecies – some of questionable legitimacy – they are grouped. Even the groupings are confused.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

At present, BOW divides the 21 subspecies into 5 groups. Of relevance to the PNW, oregonus is in the oregonus Group, curtatus is in the maculatus Group, and arcticus is by itself, presumably because it the only Spotted Towhee that is entirely migratory and it also shows the most sexual dimorphism – that is, the female arcticus is quite distinctive.

(There are other Mexican subspecies separate from all of this, such as soccorroensis, which has been considered a separate species altogether.)

Because eBird uses the BOW approach, birders in PNW coastal regions encountering a heavily-spotted Spotted Towhee typically see these options on their app:

By “maculatus Group,” eBird, at least in the PNW, implies curtatus. Though arcticus is not listed, it does tempt birders to figure out how to distinguish arcticus from curtatus, because simply using “maculatus Group” on eBird implies the bird is not arcticus.

Oregonus is largely resident (though some go south in winter). Curtatus retracts from the northernmost part of its breeding range. Highly migratory, arcticus winters entirely south of its breeding range. Both are candidates to visit the West Coast of Cascadia, though curtatus is far more likely.

Despite its proximity (and the BOW range map), there are no confirmed eBird records of arcticus in Washington, and Wahl et al (2005), Birds of Washington, assert only oregonus and curtatus are expected. British Columbia has just two winter records for arcticus (2014 and 2016), both from south Vancouver Island, and one July record from just north of the Washington/Idaho border (perhaps based on the BOW map?).

Peter Pyle’s Identification Guide to North American Birds, 2nd Edition (2023) suggests a very different taxonomy (though tentative, as we all still await a DNA study). His 1st edition was similar to BOW, but even then he had arcticus with curtatus in what he called the Interior Group. In his 2nd edition, oregonus is limited to just itself; the rest are in the coastal megalonyx Group. (Peter tells me he’s suggesting reducing Spotted Towhee’s 21 subspecies down to seven, based on morphology.) As with his 1st edition, all the interior subspecies north of Mexico City are in the same group, which he now calls the arcticus Group. The maculatus Group is reduced to just four subspecies in southern Mexico and Guatemala.

By putting curtatus and arcticus together in the same group (and suggesting they be merged?), Pyle makes our lives easier – we don’t need to worry about the identification challenge to use the eBird subspecies offerings. Except Pyle calls it the arcticus Group, while eBird calls it the maculatus Group.

Let’s set aside the taxonomic and range map questions. Can we even tell them apart? Answer: sometimes.

Identification

Focusing on oregonus, curtatus, and arcticus, I’m relying on BOW, Wright, Pyle 1st and 2nd editions, photos on eBird, and personal observations (at least for the first two subspecies). Note that upperpart color tone varies depending on lighting, and the differences are subtle. Likewise, dorsal spotting appears to vary tremendously across individuals, and varies with angle of view and posture of the bird due to feather ruffling. Tail spots (the big white spots on the underside) may be the most definitive, yet there is overlap between forms and often they are difficult to see.

These sources also discuss how pale or bright the rufous flanks are. I’ve not included this, as the photos seem quite variable in this regard, probably due to lighting.

Of all the Spotted Towhee subspecies, Sibley only illustrates oregonus (which he calls the Pacific Northwest form) and arcticus (the Great Plains form), the least- and most-spotted forms.

| oregonus | curtatus | arcticus | |

| Upperpart color tone | Male: glossy black; any streaking/mottling variable, but often quite limited. Female: dull black, sometimes with a hint of brown, with faint bold black and dark gray streaks on the back. | Similar to oregonus, but less glossy, more flat black in male. | Male: dull to grayish black with bold black and gray streaks on back. Faint olive tone to rump. Female: brownish; with narrow blonde streaks on back. |

| Dorsal spotting | White spots largely limited to the shoulder area, with a line of white spots along the scapulars; back largely dark. | White spots coalescing into bright white streaks in shoulder area, with smaller spots extending onto back. | Similar to curtatus with even more white spotting. |

| Tail spots | About ¼ to 40% the length of the tail. (Pyle: 12-25 mm long on r6) | About 1/3 to ½ the length of the tail. (Pyle: 22-35 mm long on r6) | Can be ½ the length of the tail or more. (Pyle: 27-42 mm long on r6) |

The photos below are mine or from eBird. It is frustratingly difficult to find photos of females in summer when they should be on their breeding range, and thus known.

Songs

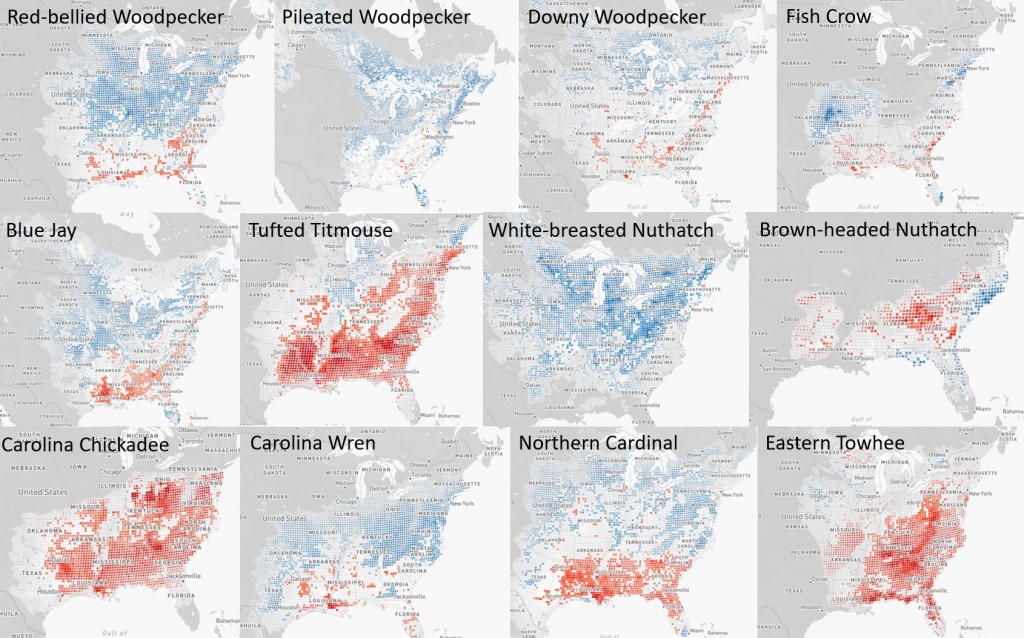

An analysis of songs of their songs suggest a different story — that oregonus and curtatus are very close to each other, but arcticus is quite separate, and with aspects similar to Eastern Towhee.

Spotted Towhees give two types of songs: a buzz or trill; and a slower electronic rattle or what I call the “shaka-shaka” song (example: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/587645701). I focus only on the former, and limit my window to May thru July, focusing on breeding birds in their summer range. They all give a distinctive “mew” call, quite different from Eastern Towhee, and rarely a few odd calls, such is a sharp “piew” that sounds like an Evening Grosbeak (example: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/447207011)

On to the buzz or trill songs. There are basically three different types:

- The buzz (dark green on the map). Example: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/584320661. This is often too fast to see the distinctive notes (vertical lines) on an eBird sonagram, unless it’s a very high quality recording. It seems more common on the Pacific slope (thus, oregonus), but is also given in the curtatus range. I could lump #1 and #2 here, as there seems to be a cline between them.

- The fast trill, often with a high-pitched introductory accent note or squeak (light green on the map). Example: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/464938911. The accent note seems more common and pronounced in the interior (the curtatus range). The same bird can give both the buzz and the fast trill.

- The trill with 2 to 6 sweet or scratchy intro notes, or even an intro trill (light blue on the map). Example: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/104621711. This song is the only one recorded on eBird in the arcticus zone, and it may be diagnostic for arcticus. Birds further east and around the Black Hills seem more likely to have more than two intro notes or an intro rattle. This song can be quite similar to Eastern Towhee, though Eastern typically has two different intro notes. With arcticus, the intro notes are alike. I found one exception, an arcticus with two different intro notes: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/220722981.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The map of song types also suggests the BOW map of subspecies is indeed off. The song type I’m associating with arcticus seems largely limited to east of the Rockies, though it does cross the Continental Divide and extend further west near Idaho Falls and also into eastern Utah near Dinosaur National Monument (not on map). That is beyond the scope of this post.

Summary

A heavily-spotted Spotted Towhee in western British Columbia or Washington, presumably in winter, is far more likely to be curtatus than arcticus. In eBird you would choose “maculatus Group,” even though, for Pyle, that would mean a form from Oaxaca or further south. Identification can be made by the back spotting and size of tail spots, though both are subject to overlap in appearance.

arcticus vs curtatus

arcticus can be separated from curtatus if: 1) it sang its distinctive song (unlikely in winter?); 2) the tail spots were large, more than 1/2 the tail length; 3) this was supported by a streaked back; and/or 4) it was a female, which are distinctive.

Thanks to David Bell and the Cascadia Advanced Birding Facebook group for alerting me to Pyle’s treatment of these birds, and for inspiring me to do this deep dive. And thanks to all who posted pics and audio to eBird! I’ll never looks at towhees the same again.

References

Bartos Smith, S. and J. S. Greenlaw (2020). Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.spotow.01

Dunn, J.L. and Alderfer, J. eds., 1999. Field guide to the birds of North America, Third Edition. National Geographic Books.

Pyle, P., 2023. Identification guide to North American birds: a compendium of information on identifying, ageing, and sexing” near-passerines” and passerines in the hand. 2nd Edition. Slate Creek Press.

Pyle, P., 1997. Identification guide to North American birds: a compendium of information on identifying, ageing, and sexing” near-passerines” and passerines in the hand. Slate Creek Press.

Wahl, T.R., Tweit, B. and Mlodinow, S., 2005. Birds of Washington.

Wright, R., 2019. Peterson reference guide to sparrows of North America. Peterson Reference Guides.