Sunset from the Central Valley, looking toward the Coast Range through the smoke of a million trees.

As I write this, helicopters are passing overhead in a dim gray-brown sky. The sun is a pink orb over the western horizon. It is 97 degrees at 7pm. The people of California sit like frogs in a slowly boiling pot.

Average temperature for July and August, here in Davis, is 93 degrees. But in the past 34 days, it was only below that six times. July 2018 was the hottest month in the history of the state.

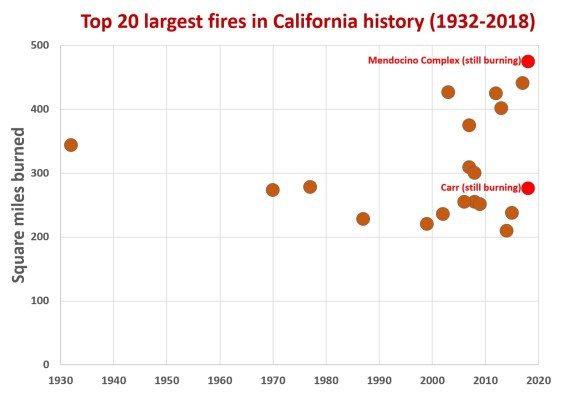

Such climate change was predicted, with great accuracy, by both oil companies and government scientists back in the 1980s, and even earlier. The consequences of this included more extreme weather, more drought, shorter rainy seasons, earlier snow melt, longer fire seasons, and larger fires. All that is coming to pass in such dramatic fashion that new records are set each year.

[CLICK TO ENLARGE GRAPHS]

Note: There were more mega-fires in November, 2018, shortly after I wrote this. These graphs are updated in a more recent blog post “Hell in Paradise: Why the Camp Fire was the largest climate-induced mass mortality event in modern history”

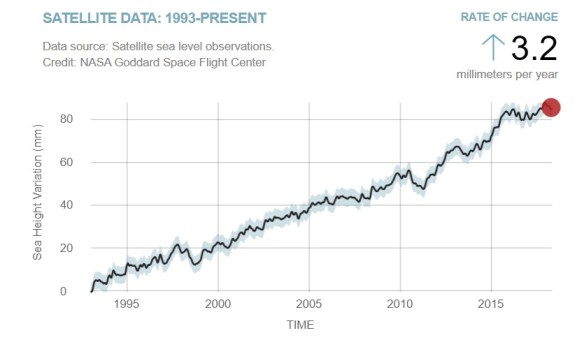

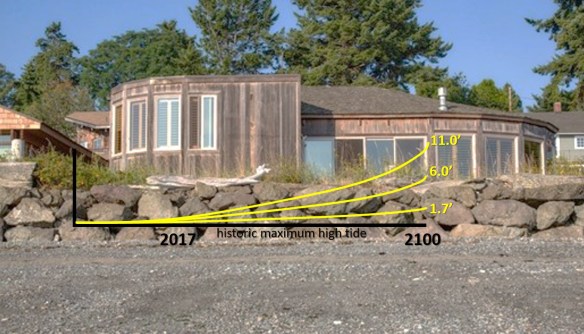

In 1988, scientists were excited– and alarmed– to see the first indications of a warming climate. Now, graphs illustrating climate change need no statistical analysis. They are obvious to a child, ramping steeply up with each passing year.

In 1988, scientists were excited– and alarmed– to see the first indications of a warming climate. Now, graphs illustrating climate change need no statistical analysis. They are obvious to a child, ramping steeply up with each passing year.

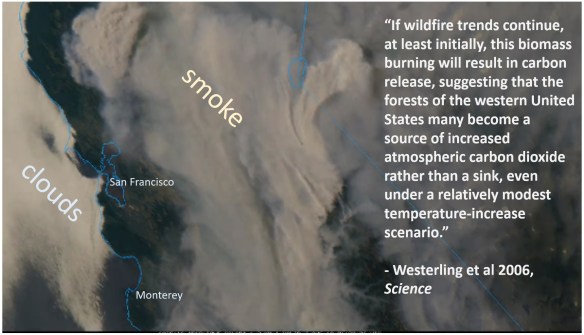

A conservative talking point seems to be that this dramatic increase in fires is not due to climate change, but to poor forest management. While this has been an issue for over a hundred years, this question was the prime focus of Westerling et al 2006 in Science, where he concluded that longer hotter summers and shorter drier winters were indeed to blame. There were increased fires even in areas without poor management– or any management at all. Where there has been poor forest management, climate warming has acted as a “force multiplier” to make fires even worse. One could only imagine how easy it would be to write that paper now, twelve years later, with plenty of new eye-popping data points. Thirteen of California’s 20 largest fires have occurred since Westerling sent his paper to the publisher.

Perhaps the best illustration of the combined effect of poor forest management and climate change comes from this 14-minute Ted talk given by Paul Hessburg in 2017.

Using a useful forest diagram, he explains how Native Americans regularly burned underbrush and maintained an open forest/meadow ecosystem that effectively prevented large wildfires. In the late 1800s, with the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans, the advent of cattle that ate the grass, and the US Forest Service suppressing fires and logging the largest trees, our forests changed from a mosaic of tough old trees surrounded by natural fire breaks to a solid crop of young growth. Add drought, heat, and an ignition source, and you see the results above.

The solution, regardless of how much you attribute large fires to climate change or management, is the same. We need to re-create the balance of the past thru the protection of large trees and prescribed burns. We need to create meadows and healthy forests. Some Native communities in northern California are planning to do this.

This all assumes that we get enough rain in winter and cool temps in summer to allow re-growth. Otherwise, the current fires may be transforming California’s mountain habitats into something resembling the mountains of Nevada and Arizona in the span of a decade.

knew pretty much what we now know today. They have been studying, researching, and modeling climate change as a result of their greenhouse gas emissions for over 50 years. Their research was in concert with the scientific community and decades ahead of public knowledge of the problem. Their predictions were typically exactly in line with the rest of the scientific world, and actually more aggressive than predictions by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

knew pretty much what we now know today. They have been studying, researching, and modeling climate change as a result of their greenhouse gas emissions for over 50 years. Their research was in concert with the scientific community and decades ahead of public knowledge of the problem. Their predictions were typically exactly in line with the rest of the scientific world, and actually more aggressive than predictions by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Watching the World Melt Away: The future as seen by a lonely scientist at the end of the earth.” The article was about seabird biologist George Divoky and his decades of work studying the black guillemot, a high arctic seabird, on Cooper Island off the coast of Barrow, Alaska. The guillemots were struggling to feed their chicks. Their preferred food, Arctic cod, lived at the edge of the sea ice. In the past, this was five miles from the island. Now it was thirty. Divoky, moreover, found himself sharing his tiny island with several hungry polar bears stranded by the vast expanse of open water. At the time, the story was one of the first concrete examples of climate change impacting an ecosystem in way that was easily seen and understood.

“Watching the World Melt Away: The future as seen by a lonely scientist at the end of the earth.” The article was about seabird biologist George Divoky and his decades of work studying the black guillemot, a high arctic seabird, on Cooper Island off the coast of Barrow, Alaska. The guillemots were struggling to feed their chicks. Their preferred food, Arctic cod, lived at the edge of the sea ice. In the past, this was five miles from the island. Now it was thirty. Divoky, moreover, found himself sharing his tiny island with several hungry polar bears stranded by the vast expanse of open water. At the time, the story was one of the first concrete examples of climate change impacting an ecosystem in way that was easily seen and understood.

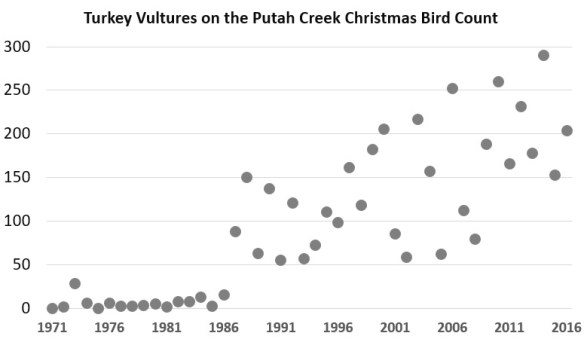

The Putah Creek Christmas Bird Count, an annual effort to count all the birds in a 15-mile diameter circle near Winters on one day each December, has tracked winter bird populations since 1971. In recent years, the number of neotropical migrants found on the count has swelled. These include warbling vireo and Wilson’s and Townsend’s warblers, in addition to the species mentioned above. Perhaps the most dramatic shift in the count data has been with the turkey vulture. With the absence of tule fog, these birds, which rely on warm thermals to give them some lift, have gone from sparse, rarely more than 15 birds on a count through 1985, to over 150 individuals per count in each of the past eight years.

The Putah Creek Christmas Bird Count, an annual effort to count all the birds in a 15-mile diameter circle near Winters on one day each December, has tracked winter bird populations since 1971. In recent years, the number of neotropical migrants found on the count has swelled. These include warbling vireo and Wilson’s and Townsend’s warblers, in addition to the species mentioned above. Perhaps the most dramatic shift in the count data has been with the turkey vulture. With the absence of tule fog, these birds, which rely on warm thermals to give them some lift, have gone from sparse, rarely more than 15 birds on a count through 1985, to over 150 individuals per count in each of the past eight years. A warming climate is expected to create more increases than decreases in bird life in Yolo County. This is because species diversity is greatest in the tropics. As bird ranges shift north, we expect to see more arrivals than departures. Among the departures are some northern species that are growing scarcer in winter. Most notable is rough-legged hawk, a tundra species that journey south to agricultural areas to eat rodents in winter. They have, however, become decidedly hard to find in recent years, perhaps finding the Willamette Valley and other more northern valleys suitable for their wintering grounds. Another species to watch is the beautiful cedar waxwing, which descend on fruits and berries in the winter months. The more they can find food in the north, the less likely they will come this far south. They are erratic from year to year, however, so it is too early to identify a trend.

A warming climate is expected to create more increases than decreases in bird life in Yolo County. This is because species diversity is greatest in the tropics. As bird ranges shift north, we expect to see more arrivals than departures. Among the departures are some northern species that are growing scarcer in winter. Most notable is rough-legged hawk, a tundra species that journey south to agricultural areas to eat rodents in winter. They have, however, become decidedly hard to find in recent years, perhaps finding the Willamette Valley and other more northern valleys suitable for their wintering grounds. Another species to watch is the beautiful cedar waxwing, which descend on fruits and berries in the winter months. The more they can find food in the north, the less likely they will come this far south. They are erratic from year to year, however, so it is too early to identify a trend.