Birds, because of their mobility, are considered to be fairly adaptable to climate change. They evolved in the aftermath of two of the world’s most catastrophic warming events (the K-T extinction and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum), spreading to the Arctic, crossing continents, and evolving along the way. While those warming events took place over tens of thousands of years, the current warming is happening in the space of a couple hundred, with noticeable changes in climate within the lifespan of a single bird.

There will be winners and losers. Generalists, and species that enjoy warmer weather, are likely to be winners. Those with narrow food or habitat requirements, especially those dependent on the ocean or the Arctic/Antarctic, will likely be losers. Although counter-intuitive, it is primarily non-migratory resident species that seem to be more adaptable to a changing climate.

Recent studies

Studies of climate impacts on western North American birds using past data are limited, but some focusing on California were recently published. Iknayan and Beissinger (2018) showed that, over the last 50 years, “bird communities in the Mojave Desert have collapsed to a new, lower baseline” due to climate change, with significant declines in 39 species. Only Common Raven has increased. Furnas (2020) examined data from northern California’s mountains, showing that some species have shifted their breeding areas upslope in recent years. Hampton (myself) (2020) showed increases in many insectivores, both residents and migrants (from House Wrens to Western Tanagers), in winter in part of the Sacramento Valley over the last 45 years. These changes, particularly range shifting north and out of Southwest deserts, is predicted for a wide number of species.

The invasion of the Pacific Northwest

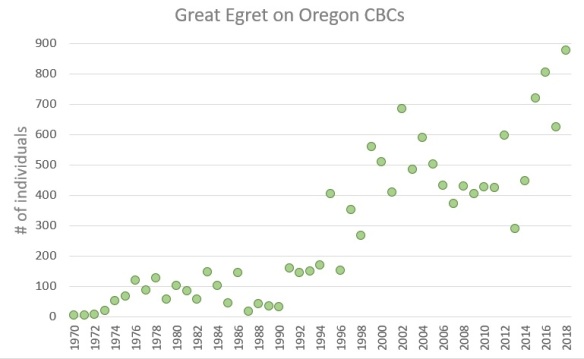

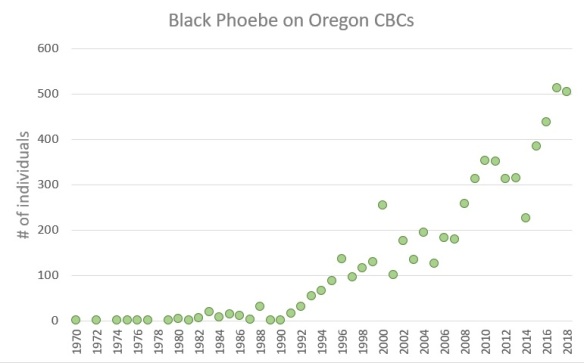

Here I use Christmas Bird Count (CBC) data to illustrate that some of California’s most common resident birds have expanded their ranges hundreds of miles north into Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia in recent years. The increases are dramatic, highly correlated with each other across a wide range of species, and coincide with rapid climate change. They illustrate the ability of some species to respond in real time.

In parts of Oregon and Washington, it is now not unusual to encounter Great Egret, Turkey Vulture, Red-shouldered Hawk, Anna’s Hummingbird, Black Phoebe, and California Scrub-Jay on a single morning—in winter. A few decades ago, this would have been unimaginable. Some short-distance migrants, such as Townsend’s Warbler, are also spending the winter in the Pacific Northwest in larger numbers.

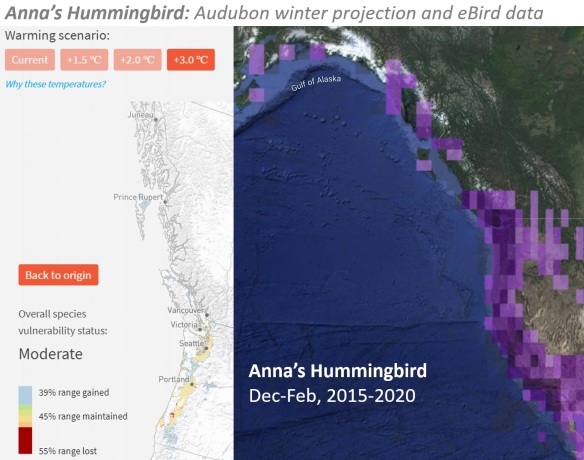

The following graphs, showing the total number of individuals of each species seen on all CBCs in Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and (in one case) Alaska, illustrate the range expansions. Adjusting for party hours scarcely changes the graphs; thus, actual numbers of individuals are shown to better illustrate the degree of change. The graphs are accompanied by maps showing predicted range expansions by the National Audubon Society, and recent winter observations (Dec-Feb) from eBird for 2015-2020.

These range expansions were predicted, though in some cases the recent trends exceed even projected scenarios under 3.0C increases in temperature.

Let’s begin with the climate. Canada as a whole has experienced 3.0C in temperature increases in winter. British Columbia has experienced an average of 3.7C increase in Dec-Feb temperatures since 1948. The greatest increases have been in the far north; increases in southern British Columbia, Washington and Oregon have been closer to 1.5C.

Average nationwide winter temperatures deviation from average.

Great Egret

Great Egrets on Oregon CBCs have increased from near zero to nearly 900 on the 119th count (December 2018 – January 2019).

CLICK ON GRAPHS TO ENLARGE

But their expansion, which took off in the early 1990s into Oregon, is now continuing in Washington, with a significant rise beginning in the mid-2000s. Great Egrets occur regularly in southern British Columbia, but so far have eluded all CBCs.

They have not quite fulfilled the full range predicted for a 1.5C increase, but are quickly on their way there.

Turkey Vulture

Turkey Vultures began increasing dramatically in winter in the Sacramento Valley of California in the mid-1980s, correlated with warmer winters and a decrease in fog. Prior to that, they were absent. Now, over 300 are counted on some CBCs. That pattern has been repeated in the Pacific Northwest, though about 20 years later. Both Oregon and British Columbia can now expect 100 Turkey Vultures on their CBCs. Curiously, Puget Sound is apparently still too cloudy for them, who prefer clear skies for soaring, though small numbers are regular in winter on the Columbia Plateau.

Red-shouldered Hawk

Red-shouldered Hawks have increased from zero to over 250 inviduals on Oregon CBCs, taking off in the mid-1990s.

Twenty years later, they began their surge into Washington. It’s a matter of time before the first one is recorded on a British Columbia CBC.

Twenty years later, they began their surge into Washington. It’s a matter of time before the first one is recorded on a British Columbia CBC.

While their expansion in western Washington is less than predicted, their expansion on the east slope, in both Oregon and Washington, is greater than predicted. This latter unanticipated expansion into the drier, colder regions of the Columbia Plateau is occurring with several species.

Anna’s Hummingbird

If this invasion has a poster child, it’s the Anna’s Hummingbird, which, in the last 20 years, have become a common feature of the winter birdlife of the Pacific Northwest. Their numbers are still increasing. While much has been written about their affiliation to human habitation with hummingbird feeders and flowering ornamentals, the timing of their expansion is consistent with climate change and shows no sign of abating. Anna’s Hummingbirds are not expanding similarly in the southern portions of their range. The sudden rate of expansion, which is evidenced in most of the species shown here, exceeds the temperature increases, suggesting thresholds are being crossed and new opportunities rapidly filled.

The expansion of the Anna’s Hummingbird has now reached Alaska, where they can be found reliably in winter in ever-increasing numbers.

The range expansion of the Anna’s Hummingbird has vastly outpaced even predictions under 3.0C. In addition to extensive inland spread into central Oregon and eastern Washington, they now occur across the Gulf of Alaska to Kodiak Island in winter.

Black Phoebe

Non-migratory insectivores seem to be among the most prevalent species pushing north with warmer winters. The Black Phoebe fits that description perfectly. Oregon has seen an increase from zero to over 500 individuals on their CBCs.

With the same 20-year lag of the Red-shouldered Hawk, the Black Phoebe began its invasion of Washington.

The figure below illustrates two different climate change predictions, using 1.5C and 3.0C warming scenarios. While nearly a third of the Pacific Northwest’s Black Phoebes are in a few locations in southwest Oregon, they are increasingly populating the areas predicted under the 3.0C scenario.

Townsend’s Warbler

Migrant species tend not to show the dramatic range expansions of more resident species – and short-distance migrants show more range changes than do long-distance migrants. Townsend’s Warblers, which winter in large numbers in southern Mexico and Central America, also winter along the California coast. Increasingly, they are over-wintering in Oregon and, to a lesser degree, Washington. This mirrors evidence from northern California, where House Wren, Cassin’s Vireo, and Western Tanager are over-wintering in increasing numbers. These may be next for Oregon.

Townsend’s Warblers are already filling much of the map under the 1.5C warming scenario, though their numbers on CBCs in Washington and British Columbia have yet to take off.

California Scrub-Jay

Due to problems with CBC data-availability, I have no graph for the California Scrub-Jay. Their northward expansion is similar to many of the species above. Their numbers on Washington CBCs have increased from less than 100 in 1998 to 1,125 on the 2018-19 count. eBird data shows they have filled the range predicted under the 3.0C scenario and then some, expanding into eastern Oregon, the Columbia Plateau, and even Idaho.

Other species

Other species which can be expected to follow these trends include Northern Mockingbird and Lesser Goldfinch. (See more on the expansion of the Lesser Goldfinch here.) White-tailed Kite showed a marked increased in the mid-1990s before retracting, which seems to be part of a range-wide decline in the past two decades, perhaps related to other factors.

Curiously, three of the Northwest’s most common resident insectivores, Hutton’s Vireo, Bushtit, and Bewick’s Wren, already established in much of the range shown on the maps above, show little sign of northward expansion or increase within these ranges. The wren is moving up the Okanogan River, and the vireo just began making forays onto the Columbia Plateau. Both of these expansions are predicted.

Likewise, some of California’s oak-dependent species, which would otherwise meet the criteria of resident insectivores (e.g. Oak Titmouse), show little sign of expansion. Oaks are slow-growing trees, which probably limits their ability to move north quickly. Similarly, the Wrentit remains constrained by a barrier it cannot cross—the Columbia River.

Call it the invasion of the Northwest. Call it Californication. Call it climate change or global warming. Regardless, the birds of California are moving north, as predicted and, in some cases, more dramatically than predicted.

Great job, Steve. Thanks for furnishing quantification for what we have seen happening.

LikeLike

Thank you Dennis. I plan to cover the demise of the Mojave next.

LikeLike

Very good piece. Bewick’s Wren has had a very significant expansion in eastern Oregon since the 1960s. Perhaps it doesn’t show in CBC results. Bushtit has had a smaller expansion, from northern Malheur County in the 1940s to Hells Canyon in the 2010s. Hutton’s Vireo is suddenly showing up at scattered sites in e Oregon, with most records in the last ten years. It isn’t clear what population is the source. Great Egret, RS Hawk and Black Phoebe have greatly expanded their breeding populations in w Oregon since the 1970s, when the hawk wasn’t present at all and the egret and phoebe barely. Finally, Lawrence’s Goldfinch is starting to be seen more often in the Rogue Valley and has apparently bred once. California Thrasher has been found on territory there in 2019. Great-tailed Grackle now breeds regularly at several sites in the southern third of Oregon. And more to come, no doubt.

LikeLike

@Alan, and there is rumor they bred at that site this past summer.

LikeLike

The Thrasher that is.

LikeLike

wow– thanks Alan! Larry G and thrasher, wow!

LikeLike

Great stuff, Steve,

Down south, we’ve noticed a decline in numbers for a variety of wintering birds from up north. I wonder how much of that is due to fewer birds migrating this far south due to climate change.

LikeLike

interesting; which species? Here in the Sacramento Valley we have a significant uptick in over-wintering House Wrens and Turkey Vultures, which used to be absent or nearly absent in winter. And over-wintering Western Tanagers, Black-thr Gray Warblers, and Cassin’s Vireos are now regular, though rare. I think 4 different CAVI last month in my county.

LikeLike

Steve: Interesting post (and blog). I couldn’t help but notice in your Anna’s Hummingbird CBC graph that the absolute numbers of ANHU counted in the three areas north of CA (OR, WA, & BC) have been consistently highest in BC and lowest in OR, the reverse of what one might expect. I wonder what is going on with that?

LikeLike

Yeah, I noticed that as well. I think it may be a function of effort. At the same time, the Victoria count produces like 700 ANHU. Must be those gardens!

LikeLike

Steve,

Thanks for your efforts in compiling this. Although I agree that most of what you state is influenced by milder winters, I would disagree in some cases that these are all that important. Part of the issue is that in parallel with warming winters there has been an on-going increase in human population in the Pac NW and N California the last 100 years from very low numbers with the resulting increase in forest clearing and agriculture that have created habitat that helps a number of species. As you point out, Oak Titmouse (and California Towhee) haven’t show any major movement N, nor have California Thrasher (maybe just starting but that species already occurred very close to the OR border and this might be a random event) or Nuttall’s Woodpecker. The most likely reason for this is that these species require oak woodland and chaparral to generate and these changes could take many decades.

If we take the example of Black Phoebe, this is a species that largely nests on man-made structures like bridges. Although I agree that it’s spread required the recent warming trend, I doubt it would have spread so dramatically without European colonization to create all those nest sites.

The three species I specifically question are Scrub Jay, Anna’s Hummingbird, and Great Egret. Scrub Jays were originally limited back in the 60s around Portland to areas of oaks such as Oak Island on Sauvie’s Island. However, they started agressively expanding into the urban/suburban areas around that time and were already common in Portand by the time I arrived there in the late 80s. This is before the mild winter trend kicked in the early 90s. I would argue that there spread up through the Puget Sound simply reflects their new affinity for suburbs. It’s not like W Washington was colder than Sauvie’s Island.

Anna’s Hummingbird also spread aggressively much earlier and this is clearly a result of feeders and ornamental planting.

I think Great Egret is a species that kicked into a dynamic expansion mode following its recovery from plume hunters and the general reduction in hunting. Herons/Egrets are doing well generally in Europe and USA. In Europe, Great Egret has expanded from E Austria to colonize all of Western Europe. Many of the areas it has colonized, like Spain and S France, are significantly warmer than Austria so I don’t think one can claim climate change as being a core driver.

LikeLike

Nick,

Thanks for your comments. Clearly anthropogenic factors have played contributing and necessary roles for some of these species’ expansions. If the birds are trying to climb a ladder going north, these factors have provided the rungs. And some, like oak-dependent species, don’t have those rungs yet (slow-growing rungs!). I would argue that many of these human factors — bridges, ornamental plantings, etc.– have been around far longer than the species expansions. Most of these species didn’t really expand north until after 2000, some by 1990. The rungs have been there, but only more recently are the species taking advantage of them.

LikeLike

Scrub Jays in the mid-Willamette Valley were quite common when I was growing up in the Albany-Salem-Jefferson area – in current and former oak-savanna that had pretty much been replaced since the 1840s by agriculture and residential. My father, who grew up near Ankeny NWR, noted that Scrub Jays were uncommon there in the 1930s; by the late 1950s they were back yard birds.

LikeLike

Jon, Thanks for that information– that goes back a long ways, preceding the map I made specifically about Calif Scrub-jays. See this blog post especially about them: https://thecottonwoodpost.net/2021/10/28/mapping-the-expansion-of-the-california-scrub-jay-into-the-pacific-northwest/

LikeLike

Pingback: Becoming Arizona: How climate change is transforming California thru fire | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: Mojave Desert bird populations plummet due to climate change | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: The song of the Lesser Goldfinch: Another harbinger of a warming climate | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: Goodbye California: Reminisces of a climate refugee | The Cottonwood Post

Interesting paper. I would like to know where you received your information on turkey vultures wintering on the Columbia Plateau. They do show up in winter along our coast and other spots, but I have very little knowledge of them from the Columbia Plateau in winter.

LikeLike

Diann, My data for TUVU on the Columbia Plateau is purely from the CBCs in that area; that’s where many of WA’s TUVUs on the CBCs are recorded.

LikeLike

Pingback: Mapping the expansion of the California Scrub-Jay into the Pacific Northwest | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: Carolina Wren + Climate Change vs the Polar Vortex | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: Northward expansion of Northern Cardinal, Carolina Wren, Tufted Titmouse, and Red-bellied Woodpecker | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: Heading south for winter, more birds are choosing the Pacific Northwest | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: eBird Trends maps reveal dramatic northward range shifts in Eastern species | The Cottonwood Post

Pingback: The Limpkin: An invasive species in a changed world | The Cottonwood Post